Bunks in airline cabins harken back to the glamorous, glory days of flying, the long flights where your white-gloved flying butler would show you to your sleeping quarters and draw the curtains of the flying cocoon before you emerged, hours later, at either your destination or at an exotic stopover. 18-hour-plus flights are the new normal now, with the definitions of long-haul and ultra-long haul stretching ever longer. So is it time to revisit the idea of bunks?

As Daniel Baron of LIFT Aero Design explains, “ultra-long-haul used to be ultra-niche. But with Russian airspace no longer used, some very large markets – such as East Asia to Europe or China to the east coast of North America – now have flight times of 15–17 hours. And the situation is not likely to return to normal anytime soon.”

“Plus, rising fuel costs mean higher fares,” Baron notes. “The current comfort-price equation will be tested. Will travellers say ‘if I’m paying this much for economy class, I expect to be flying flat’? In that scenario, if the economics work, bunks as an entirely new class or product could become the next big disruptor. And once you know flat, it’s impossible to go back.”

Baron’s best-known recent work is perhaps the renewing of Philippine Airlines’ cabins, and coincidentally enough that was the carrier to offer the last proper bunks, on its Boeing 747-200B, delivered in the early 1980s, in which first-class passengers would leave their reclining armchairs in the nose of the plane and climb up to either an upper, lower or side bunk in the jumbo’s small top deck.

For a long-haul-focused airline, bunks certainly sound like an attractive concept, but functionally, certifying bunks in the age of 16G requirements is complicated, particularly around accessibility and egress. Their concept of operations is equally complex: who are they for, how should they be used, and how much will passengers pay?

And, as Baron says, one of the key questions has always been for segments that are mostly daytime: “Would there be a pronounced lack of demand for beds, with passengers preferring a lounge or upright position to work, read, eat, and so on, and occasionally snooze but without moving to a dedicated bed?”

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Air New Zealand had been working on its Economy Skynest three-tier, six-bunk system for several years. Skynest has so far been presented only in isolation as a mockup, but in the centre section of the main cabin floor, with economy class seats ahead of it. The airline did not respond to a request for an update before this piece went to press.

So whither Skynest? Air NZ is presently working on a new configuration for its B787-9 aircraft, with the details of its new business suite leaking at the end of April via a US DOT accessibility filing. If the Economy Skynest were to be aimed at these aircraft too, it would be impressive if the certification of the product, including for accessibility, had not leaked as well. The airline’s forthcoming B787-10 fleet, which would be the other candidate for the debut, is stuck in the current Boeing Dreamliner production stoppage. Might the Skynest re-emerge on the other side of Covid?

The bunk market

The prospective market for bunks differs based on the class of service. In first class and business class, modern long-haul seats go fully flat, most have direct access to the aisle for every passenger, and a growing number offer privacy doors that create mini-suites. The passenger experience benefits of a bunk versus an individual seat that turns into a bed are, as a result, minimal.

Indeed, as Martin Darbyshire of the Tangerine design house explains, the key question for bunks is: “how do you stack them in a way that actually improves the passenger experience and is genuinely better than going from a reclining chair to a lie-flat solution?”

“We’ve explored bunks on a number of occasions and never quite got there for a number of reasons,” he says.

At the other end of the aircraft is the economy bunk proposition, where the desire to get up out of increasingly cramped seats and spend part of the flight stretched out horizontally is so great that many airlines’ safety cards have to specifically point out that lying on the floor is prohibited. The demand here is clear, but the willingness to pay – both in economic and general terms – remains untested.

In the middle lies premium economy, where the ‘ow, my knees’ factor is less pressing than in regular economy, but depending on pricing and flight length there still may be demand for bunks from premium economy passengers.

Bunk operations models are complicated

On flights long enough for bunks to be an attractive proposition, passengers need to be able to enter and exit the bunk (including to stretch, visit the lavatory and so on), eat, sleep and entertain themselves.

Key questions for how bunk operations might work include whether each bunk comes with a specific assigned seat, whether any passenger can book a bunk for the whole flight, or whether a submariner-style ‘hot-bunking’ arrangement should be in effect.

If each bunk comes with a specific assigned seat, as is the case in most of the business class concepts and many of the premium economy ones, when one is in use, the other will be empty. That creates wasted inflight space that could instead be given over to a much easier convertible seat option.

If any passenger can book a bunk for the whole flight, this raises questions about how meal service works. Does the passenger return to their seat? Would passengers be given a tray in their bunk? Some sort of portable packed lunch service? A different option that might involve standing around a fold-out bar in the galley area for tapas?

One option is certification of jumpseat-style seating for bunk passengers to use during taxi, takeoff and landing (TTL), and then to show them to their bunk once the seatbelt signs are off. This seating would likely need to be further developed and refined in order to be occupied by naive users rather than by specially trained safety experts like cabin crew.

If the concept is hot-bunking, this poses a raft of complicated operation questions: how long are each of the hot-bunking sessions? Can passengers book more than one session in a row, and how much of a complication is that?

What happens during bunk switching? Does the crew come round and strip the bunks, clean the surfaces, remove any rubbish or detritus, and remake them with fresh pillows, blankets and linens? Where would all this extra bedding be stowed?

Another question is how much disruption the changeover period between hot-bunking sessions would cause for other passengers — whether those in the regular economy class seats or those who are also sleeping in bunks — especially as this would presumably occur during the quietest times of the flight, when the cabin would be dimmed, with the shades drawn.

Passenger sentiment issues might also come to the fore with various bunk operations and models.

“There might be perception of risk to one’s personal belongings,” suggests Daniel Baron, giving an example: “there’s space in the bin right at or above my economy class seat, but not at the bunk. I would want my belongings near me, and would not want to schlep them back and forth.”

Baron also makes a point about personal safety and cultural or social issues: would some passengers feel less comfortable sleeping in lower or upper bunks? How would that change in terms of social status and other personal attributes? What complications are there around gender, religious observance, and other individual characteristics of passengers? Designing with sensitivity for all these factors would clearly be needed.

Certification of bunks is a big unknown

Safety certification naturally comes up whenever any kind of bunk design is considered. Helpfully, the first big question also has a relatively straightforward answer according to the experts we talked with: it seems unlikely that bunks could ever be certified for occupation for the entire flight.

“If there are upper and lower bunks, there is potential for injury to self and others while trying to evacuate from the upper bunk, so I can’t see certification for use during taxi, takeoff and landing,” says Daniel Baron. “A more feasible scenario might be a high-density seat for taxi, takeoff and landing, and a bunk for use in between.”

Passengers would thus need to be seated for these critical phases of flight, entering a bunk only in the cruise segment. Presumably, every bunk would have a seatbelt for unexpected turbulence.

The remaining certification questions then revolve around access to the bunk and, in an emergency, egress. One comparison could be the inflight egress requirements for crew bunks, whether that is in the crown space or in a lower-level bunk area. It’s very tempting to just suggest that airlines create a version of the overhead crew rest areas for passengers, but this would get very complicated, very quickly.

“Crown spaces are not as straightforward as you might think,” explains designer Ben Orson of Orson Associates, highlighting that rest areas in the crown require an emergency escape hatch, usually concealed within a replica overhead bin.

“I’ve only looked at this in the context of the first-class environment, but anything below the hatch has to be able to withstand somebody leaping from a metre or two up onto it. So, when we were designing a meal table for JAL [for a seat below the hatch], you had to be able to stand on it, and so it had to be extraordinarily strong. I’m not quite sure what that would look like when considering dropping down on top of an economy class seat, but it would be an interesting load case.”

In terms of lower-level bunks, egress is via a ladder that usually emerges upwards into the cabin via a hatch in the floor where a passenger seat would be. On the Airbus A380, this is visible in the cabin as a missing seat, as seen in the absence of seat 70D on Qantas’ A380.

But there are real questions to ask about how much certification overlap there would be between cabin crew – who have specific height, weight and physical ability requirements for doing their job, and who are provided with special emergency egress training in order to be able to use these very compact and cramped rest areas safely — and average passengers with varying height, weight and ability levels.

Access for disabled travellers and people with reduced mobility is also a concern, particularly for any concept using the upper crown area or lower lobe of the aircraft, or where bunks are layered on top of each other and require steps for access.

It’s unclear what accessibility requirements would apply to bunks, especially if they are sold not as seats but instead as some kind of ancillary product. Would something like the US Department of Transportation’s 14 CFR Part 382.21 requirement for a minimum of 50% of the aisle seats to offer movable aisle armrests be needed, for example, in requiring some proportion of bunks to be accessible for transfer from an aisle chair?

Supply of airflow, including oxygen masks in the event of a cabin depressurisation, would also need to be engineered, as would power for lighting and, these days, power outlets for passenger devices.

Fundamentally, bunks may well serve best “as a sort of halo product”, suggests Ben Orson.

“Especially for economy class, we don’t get a lot of halo products,” he notes. “It’s a really attractive idea. But quite how how effective it is, or how much extra revenue you can expect, just from having a halo product – over and above anything you might actually get from selling the seats – is hard to quantify.”

Indeed, of all the bunk concepts Tangerine has explored, concurs Martin Darbyshire, “you end up compromising the offer, I think, in a way that doesn’t really make it adequately palatable at the moment. That’s the challenge.”

Take a look at a few other bunk designs that have emerged over the years…

AirSleeper

A bunk concept was in the first round of the 2022 Crystal Cabin Awards: the AirSleeper from Mmillenniumm, whose chairman and CEO, A. I. ‘Indi’ Rajasingham tells us that as “a tiered architecture for aircraft cabins”, AirSleeper “is positioned for several price points in the premium economy segment”.

The product essentially splits the cabin into a lower level and an upper level, each of which has seating arranged in a way reminiscent of the PriestmanGoode sofa concept which became the Collins AirLounge on Finnair.

For taxi, takeoff and landing the passenger sits in an aisle-side, forward-facing seat, and can slide slightly round to the side into a kind of armchair position. When converting to bed mode, a cushioned layer folds down from the seat in front to create a sleeping surface angled away from the aisle in a herringbone layout.

To access the upper bunk, every upper-tier passenger has a fold-out ladder, and children are catered for with a special child booster seat in what would otherwise be their parents’ footwell space. Since the upper bunk stretches to the ceiling, storage for all passengers is at the foot level at the aisle.

While the concept is interesting, the certification and evacuation pose immediate and obvious questions.

“We have carefully considered the evacuation requirements and we believe we will comply,” Rajasingham tells us. “We have also done extensive engineering to create a product that should meet the stringent structural constraints in an airframe and most importantly the safety requirements, particularly under crash conditions.”

Slumbered, not stirred

A converted military cargo aircraft may not initially sound very glamorous, but the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser was one of the ultimate aircraft for a luxury passenger experience.

The inverted figure-8 double deck fuselage provided 6,600 ft³ (187 m³) of interior space designed specifically for luxury air travel. Boeing offered flexible configurations and Teague was involved in the design. A 114-seat all-economy aircraft could be ordered, but a popular configuration was to have 75 seats, 56 of which could be converted into lie-flat sleeper berths, complete with privacy curtains, and a further 19 reclining seats.

On the luxury services, such as BOAC’s Monarch service in the 1950s, passengers had a fantastic destination space, as there was a midship spiral staircase, which led down to a horseshoe-shaped 14-seat lounge in the lower lobe area, with a bar under the stairs.

Thus sated, guests could change into their nightwear in the dressing rooms (one for gentlemen and two for ladies, all of which could accommodate three people) before retiring to their bunks. Some carriers even had a ‘Stateroom’ in a forward compartment, which converted into a bedroom for two passengers to share.

In Ian Fleming’s book For Your Eyes Only, James Bond loved the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser passenger experience, in which he could “have dinner in peace, sleep for seven hours in a comfortable bunk, and get up in time to wander down to the lower deck and have that ridiculous ‘country house’ breakfast while the dawn came up and flooded the cabin with the first bright gold of the Western hemisphere”.

Air Lair

In 2012 Factorydesign was challenged to create a fantasy concept for Contour (now Zodiac Seats UK), and devised the striking Air Lair design, which was a double-deck system of individual pods, claiming to offer 30% additional passenger accommodation in the same footprint as a single-deck layout. The concept lay somewhere between premium economy and business class.

“We did have a weather eye on creating something that had a basic intelligence about what it was suggesting a cabin could do in terms of new innovation,” explained Adam White, director of the studio. “What we were trying to say was that thinking about the cabin in layers was important.”

The concept had a very mixed reaction at its reveal at Aircraft Interiors Expo 2012, but soon after White noticed that more people were approaching him to talk about the validity of Air Lair as an idea to optimise cabin space.

Perhaps the concept was just a little ahead of its time. “That would be our ultimate wish. That people are able to look back at Air Lair and say, ‘That was the first moment I thought that what we have launched today was possible’.”

See here for a video of Adam White explaining the design

StepSeat

Jacob Innovations has been creating ideas to maximise use of the available vertical space in the cabin to enhance comfort. The company has created several ideas for several classes, all using vertical levels to increase comfort without sacrificing cabin density. The original is the StepSeat, an economy-class concept that sees alternate seats mounted on ‘steps’, which are small platforms the height of a conventional step. This arrangement increases legroom for all seats and enables occupants to recline to around 45° within the fixed shell, with an optional leg rest further enhancing comfort.

The inventor, Emil Jacob (also president of the company) says that while access to the seat looks rather narrow in the renderings, the access space is actually almost the same as a conventional economy seat at a tight pitch.

Cloud Capsule Concept

In response to the impact of the global coronavirus pandemic on aviation, a special ‘Judges’ Choice Award’ category was added for 2021, in recognition of aircraft cabin and on-board products that address the latest air travel challenges.

Toyota Boshoku made it to the final judging round with the Cloud Capsule Concept, which could offer economy passengers the option of both a seat and access to a comfortable bunk bed berth located above the window seats.

Collapsible beds for the Flying V

The Flying V, a V-shaped wing body aircraft concept that is currently under development by TU Delft in association with KLM, has a cabin in the wing that is oval-shaped in cross-section. The university has developed collapsible beds for the economy class cabin that effectively use the oval cabin space at the rear side of the wing. This configuration is optimised to work with the structural body enforcements and make it possible for three passengers to lay down horizontally.

By allowing the middle bed to slide up, and half of the bottom bed to fold down, this triple-height bunk bed can easily be converted into three seats for take-off and landing, which is a requirement for quick evacuation.

To provide ultimate bed comfort, the bunks include a built-in infotainment system, overhead display, charging points for personal electronics, a tray table and an inflatable backrest to allow for a more upright sitting position whilst in the bunk. TU Delft’s research has found that getting into the proposed beds would not be problematic, even for elderly passengers, provided they enter head-first.

A bi-level investment

High-density economy cabins have been a source of concern for IpVenture, which is not an aviation designer or manufacturer, but rather a Silicon Valley-based specialist in partnering with innovators to develop technology patents and then monetising the patents through licences and sales.

The company believes it has a space-creating solution on its hands with a design for safer and more spacious economy class seating with no loss of seat count. The key to this claimed achievement is a bi-level staggered-seat approach that increases each passenger’s space and gives them easy access to the aisle. Passengers in the lower level window seats can slide backward, allowing passengers to move behind the seats, even when the aisle seats are in a reclined position.

On the upper level, all passengers have room to walk to the aisle from the front of their seats. This space to manoeuvre also means that aircraft can be evacuated in a swift and orderly fashion, according to the company.

IpVenture believes that the design, if implemented, would deliver rested passengers to their intended destinations. As it stated, “The only thing passengers should recover from is their excitement.”

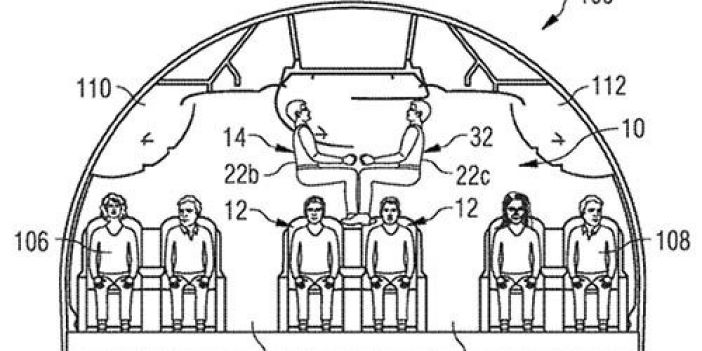

An Airbus patent

Airbus made international news in 2015 when it filed a patent application for a double-deck business class cabin. The company files around 600 patents each year, but this one really provoked strong public reaction, from oaths never to fly again if the design took to the skies, to the inevitable comparisons with sardine cans that meet most high-density ideas, and even 19th century slave ships.

The patent described rows of seats alternately arranged at lower and higher levels, with the upper ‘mezzanine’ seating making use of upper lobe space. The design makes more optimal use of available cabin space, and passengers would have flat beds and direct aisle access, so what upset the public so much? . Perhaps it was the rather unappealing patent drawings…

Flex

Tangerine developed the Flex concept as part of an airline pitch, with the design giving window seat passengers a separate bunk located above the inner seats. The two spaces are entirely separate, giving window seat customers a comfortable reclining seat for TTL and relaxing, and a separate, private sleeping area across the aisle and up five steps. While the inner passengers do not have access to the mezzanine-level bunks, their seats do convert into lie-flat beds. The concept sketches show the inner seats facing sideways in the cabin, but that is not a necessity for the arrangement to work, so long as there is sufficient space for the centre seats to be converted into flat beds.

There is clearly a big disparity in the passenger offer for window and centre occupants, which would have to be addressed in the ticket pricing. However, the concept does have a big drawback, as Martin Darbyshire, CEO of Tangerine explained: “The scary thing is that the number of seats that you get is not bigger than using a current lie-flat solution in a fairly dense form. I think that is really going to call into question the validity of the concept for a lot of airlines.”

Economy Sky Dream

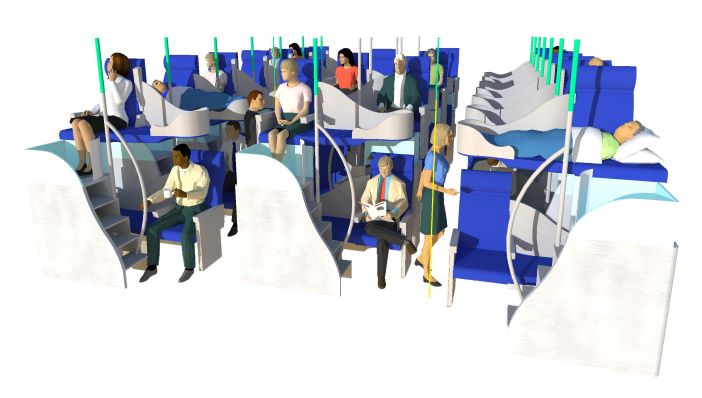

Dutch transport engineering firm, ADSE, has developed Economy Sky Dream, an economy comfort class concept for wide-bodies, with a focus on enabling sleep without impacting airline operations, cost of ownership or airworthiness. The premise sounds like a dream for long-haul travellers, so how does the concept work?

Economy Sky Dream offers three-tier bunk-beds for the centre triples in a 3-3-3 seating configuration, the centre location having the maximum cabin height, which is maximised by not having central overhead luggage bins.

During TTL and cabin service, the fore and aft layout sees passengers seated opposite each other, with their hand luggage stowed and secured under the seats. Once the cruising phase begins, crew fold away the armrests of the triple seat to form a bed surface, and then lower two further beds from above, accessible by a fold-down ladder. Each bed is 76-80in long (1.93-2.05cm) depending on the aircraft and 23.6in (60cm) wide, and features an individual PSU with USB charging port.

The result: beds for each Economy Sky Dream traveller, and more of the glorious sleep that makes ULH routes feel shorter and that helps passengers arrive at their faraway destination feeling refreshed. The downside is that there is some disruption during meal service, when the bunks have to be stowed and the bottom bunk restored to a triple seat, but that is a minor niggle.

The concept has no downside for airlines though, according to ADSE, as the modular hardware has a similar footprint to ‘economy plus’, and the bunks represent an ancillary revenue opportunity.

The company also says that the design conforms to current operational and evacuation procedures and would not represent a major certification issue.

As the hardware fits into the existing seat tracks and luggage rack suspension system, the concept would be easy to retrofit into wide-body aircraft using existing installation techniques and would not affect the residual value of aircraft.