Air transport has come under criticism as a potential factor in facilitating the spread of Covid-19 around the world. With a view to answering such criticism, the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR)) has been investigating how virus particles might actually spread within the passenger compartments of aircraft, and the effects of cabin ventilation. The organisation is hoping that its findings may help to better understand the challenges facing mobility during the Covid-19 pandemic – for air as well as rail travel – and thus contribute towards finding solutions.

DLR’s researchers, based in Göttingen, Germany, have worked in the field of cabin air conditioning for aircraft and trains for years, focusing on the comfort of passengers and the energy requirements of the systems. The scientific tools developed by the team are now being applied to research the spread of viruses within passenger cabins.

The team is only investigating the spread of physical particles that are analogous to virus-laden droplets and is unable to make any statements about the infectiousness of such droplets. The team is not factoring in the effects of aircraft cabin air filters, although this topic is being researched at their sister organisation, the DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine in Cologne, among other places.

The spread of potentially virus-laden droplets in cabins is being investigated through experiments and computer simulations. The researchers first introduce a ‘sick’ passenger into a fully occupied area and then look at how far exhaled particles are distributed.

One model uses a section of an open-plan train compartment with six rows of seats. The ‘sick’ passenger’s exhalation or coughing pattern is generated using a program that has long been used to simulate cabin airflow. This model is supplemented by the addition of aerosol particles, which then atomise and evaporate. For coughing, the team found that the atomisation process has clear parallels with the process of injecting fuel into an engine, where strong shear forces cause the droplets to disintegrate.

The parameters used, such as the exhaled lung volume (approximately one to 1.5 litres) and the size of the droplets, which range from smaller than one micrometre to several hundreds of micrometres, are derived from studies conducted by the US Federal Aviation Authority (FAA). The program calculates the distribution and range of the particles and provides a graphical representation of their propagation.

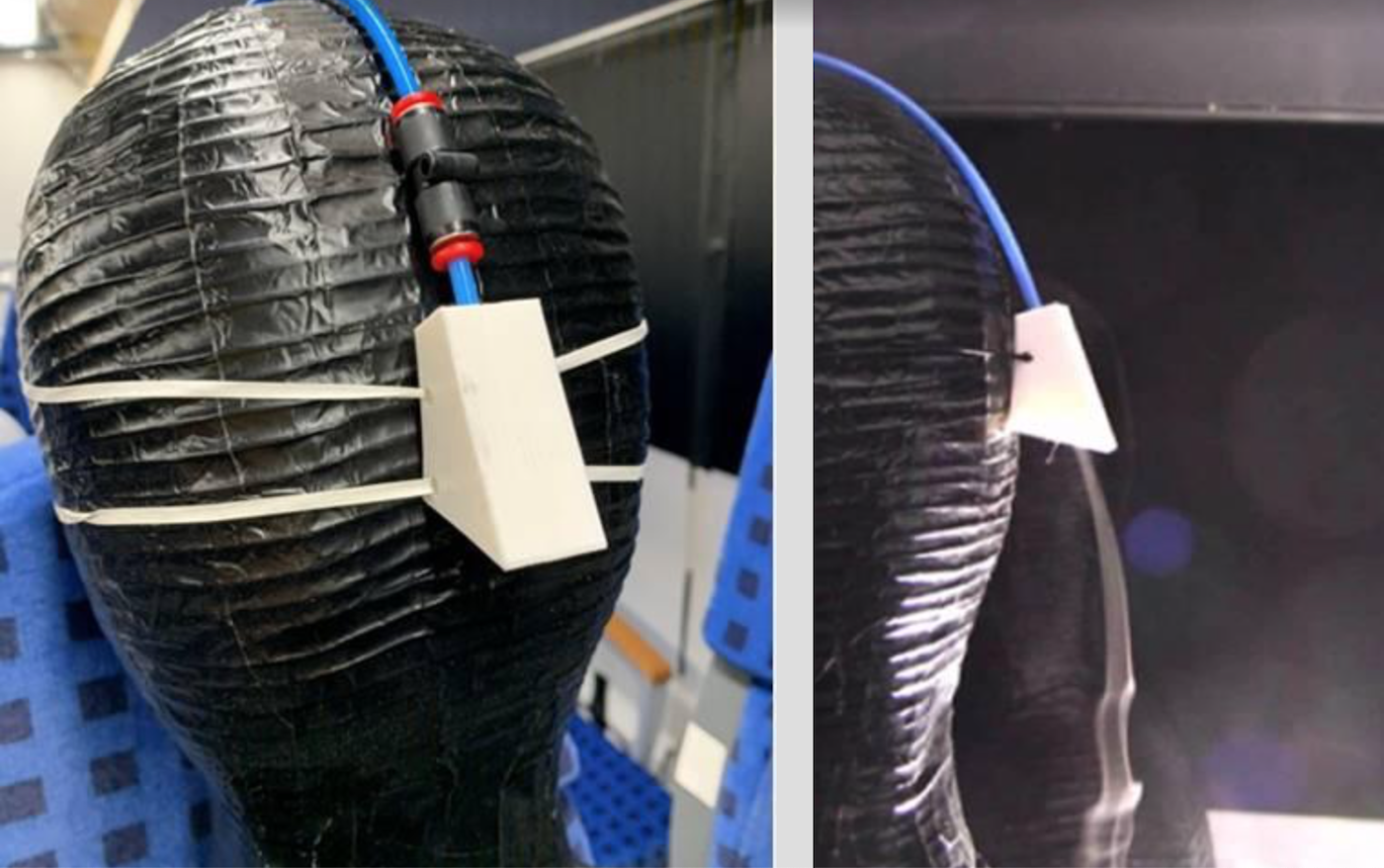

The researchers are also using a physical model for the railway carriage experiment, with 24 mannequins fitted with sensors serving as the passengers. A ‘sick’ mannequin releases air with added droplets and a tracer gas from its mouth area. High-speed cameras and gas sensors track the spread of the particles within the cabin, and the particles and their concentration are recorded at various points within the space.

Karsten Lemmer, the DLR executive board member responsible for energy and transport, and a frequent train traveller himself, stated, “Our study on mobility during the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that many people feel less comfortable travelling by public transport than they did before. This behaviour is hindering the mobility transition, which seeks to increase the use of local public transport. Our research into the spread of viruses in passenger cabins is intended to help bring some objectivity to this discussion.”

Computer simulations similar to those used for trains are also being performed for aircraft. One such experiment is soon to begin at DLR’s new aircraft laboratory in Göttingen as part of the EU ADVENT project.

Rolf Henke, the DLR executive board member responsible for aeronautics research, stated, “Aircraft cabins are self-contained systems and already have a high level of air quality control. Our research on virus spread in cabins is intended to help protect passengers from infections and find ways of making flying safe in future.”

Preliminary results from the recently initiated research studies are expected in the coming weeks. However, some of the experiments are set to continue for months. All of the findings will be published and made available to industry partners.