The US Department of Transportation (DOT) now plans to send recommendations for new rules governing the use of closed captions on video content on aircraft flying in and out of the USA to the US Secretary of Transportation this year (25 July 2015), with proposed rules to be made public in December 2015. A period for affected parties to comment on the proposed rules is scheduled to last through February 2016.The US Department of Transportation (DOT) now plans to send recommendations for new rules governing the use of closed captions on video content on aircraft flying in and out of the USA to the US Secretary of Transportation this year (25 July 2015), with proposed rules to be made public in December 2015. A period for affected parties to comment on the proposed rules is scheduled to last through February 2016.

As previously reported in Part One of this story, approximately half of the IFE-equipped global commercial aviation fleet is currently able to support closed captions. For the half that does not, the outcome of these regulations have multi-million dollar implications if the recommendations made to the DOT by the Airline Passenger Experience Association (APEX) – that closed caption capability only be required as IFE systems are replaced for other reasons – are not accepted.

For APEX’s Technology Committee – which began working with DOT on closed captions and accessible media in 2006 – the new schedule provides not only an opportunity to address the DOT’s remaining questions on the information previously submitted to the agency by APEX, and to make progress in the development of new closed caption delivery specifications, but to also make progress in another area of media accessibility of interest to DOT, that of audio descriptions of content for the blind.

And the good news for the Technology Committee is that once available for IFE utilization, descriptive audio for the blind is easily implementable under current workflow practices.

Formed in 2013 by the APEX Technology Committee, APEX’s Closed Caption Working Group (CCWG) members include airlines, experts in the field of closed captions and descriptive audio, IFEC service providers, representatives of the entertainment industry including the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), and experts in post-production.

Descriptive audio for the blind

The DOT has made APEX aware that, in addition to closed captions for the deaf, the agency is interested in IFE accessibility services for blind and partially sighted persons. APEX is currently considering specifications for descriptive audio in IFE, and is working with Boston’s National Center for Accessible Media (NCAM) and Canada’s Descriptive Video Works in this activity. Diane Johnson, president and CEO of Descriptive Video Works, has joined the CCWG to aid in the pursuit of descriptive audio solutions, along with Geoff Freed, director of technology projects & web media at NCAM. Gerald Freda, president and COO of closed caption provider CaptionMax, has joined to help finalize closed captions specifications.

Descriptive audio for the blind involves the use of extra audio narration in the soundtrack of a movie or TV program that describes important on-screen information or cues, according to Freed who, in addition to his CCWG membership, is a member of the W3C Timed Text Working Group. (Timed Text is a closed caption format codified by the W3C and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). SMPTE Timed Text 2052 and WebVTT are the standards that APEX is most likely to use).

The audio narration describes action, body language, costumes, on-screen text and any important visuals, says Freed. Using the existing soundtrack, this narration is inserted into pauses during the program narration or dialog without changing those components.

Audio descriptions for the blind are available in the USA on some of the content of all major broadcast networks and cable, according to Freed. This includes the top four commercial networks (ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox) in the top 25 broadcast markets, which must provide 50 hours per quarter of prime-time or children’s programming with audio descriptions. This Federal Communications Commission (FCC) requirement will expand to the top 60 US markets in July 2015.

“Audio description is in its infancy and will grow to closed caption levels,” according to Johnson. She also observes that Netflix’ adoption of audio description this year is an important milestone.

In addition, says Freed, cable networks with 50,000+ subscribers and the top five national non-broadcast networks – currently USA, Disney Channel, Nickelodeon, and TBS – must provide the same volume of audio descriptions. There are no current requirements for audio descriptions on IP-delivered video. Johnson says that by 2020, the US FCC will attempt to achieve 100% of nationwide broadcast coverage with audio descriptions. In the UK, says Johnson, audio description is required on 10% of broadcast programs, while Sky TV is at 40%, and 21 other channels are over 30%.

For broadcast television and DVDs, explains Freed, audio descriptions are delivered on a separate audio channel as a full-mix track (a full-mix track means that the dialog, including descriptive narration, music and effects have been mixed and balanced). In movie theaters, audio descriptions for the blind are delivered via IR/FM transmitter and use the description track only. Today, according to Freed, most major studio first-run motion picture releases are both described for the blind and captioned for the deaf. In the period between July 2013 and July 2014, at least 116 first-run movies in the US were described for the blind.

In the content delivery supply chain in IFE, delivering audio descriptions is technologically simpler than delivering closed captions. The descriptive audio track can be handled just as any other audio track, such as the Spanish, French, German or Italian track in the case of English-language movies. And though some content providers have noted that a rights definition and clearance process might be required before audio descriptions can be provided in IFE, this does not appear to be a major obstacle.

Accessibility of the pax interface

“Providing described movies/videos is one thing,” says Freed. “Accessing the descriptions during IFE playback is another. How do blind/visually impaired passengers operate a device with unmarked buttons? Or a device with no buttons?

“Accessibility solutions on the ground can and should influence solutions in the air,” adds Freed. And that includes hardware, software and Web/app structure and markup. Freed suggests considering screen readers for desktop/laptop computers and mobile devices, and talking interfaces such as kiosks, ATMs and set-top boxes. He cited Comcast Cable’s new X1 platform in the USA, and says that many other options will be available when the US FCC regulations take effect in 2016.

Freed also observes that screen readers and TTS that function through gestures rather than key/button commands might be considered, as well as screen magnifiers for some applications. An accessible user interface (UI) should have a layout which is consistent and predictable, as well as a design that considers foreground/background contrast, clutter, motion, size of targets and the labeling/meaning of targets.

Freed demonstrated a screen reader during the APEX Technology Conference in Newport Beach, California in November 2014, and an app that allows a blind user to “hear” what buttons are being pressed on a touch screen. Freed says that this kind of technology could be modified for an IFE user-interface system. “You don’t have to reinvent anything,” he says.

Some airlines seize the initiative

Two airlines that have not waited for the codification of specifications by APEX before moving to implement IFE services for the blind or visually impaired are Emirates and Air Canada. In July 2014, Emirates became the first airline to introduce audio description on several of its movies. Under a deal with Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Emirates launched its new service with 16 Disney movies including Frozen, Saving Mr Banks, Cars 2, Monsters University, Marvel’s The Avengers, Toy Story 3, and all four Pirates of the Caribbean movies.

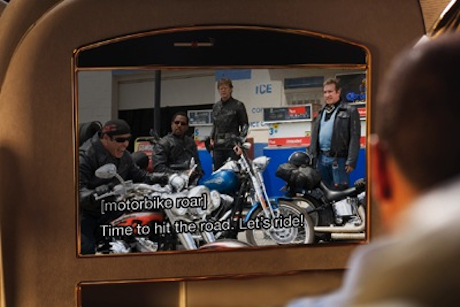

Emirates had also partnered with Disney to be the first airline to use closed captions in IFE and typically offers over 50 closed caption movies in its content set. It has now been joined in closed caption provisioning by Air Canada and a short list of others. As recently as March 2015, Delta Air Lines offered approximately 50% of its VOD movies with closed captions, including Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1, Birdman, and Horrible Bosses 2. Users of LiveTV’s 4.0 system – such as JetBlue’s newest A321 aircraft – began receiving more than 100 channels of closed captioned television content in summer 2014.

At the APEX MultiMedia Market in Prague in April 2015, Éric Lauzon, IFE manager for Air Canada, remarked about his airline’s IFE system: “Air Canada is proud to be the first airline to offer an IFE system that is fully accessible for all passengers – regardless of their hearing or visual impairment.”

Lauzon explained that Air Canada’s service provider, DTI, developed a prototype GUI designed to simplify on-screen navigation for the visually limited passenger, featuring easy swipe and touch gestures, the use of identifiable colors for users with low vision, simple commands, and physical buttons for handsets – supported by vocal instructions that can be repeated at any time.

The feature is available on Boeing 787s, which have recently been introduced to Air Canada’s fleet. Air Canada’s IFE systems are also equipped with a supply of tactile and audio selection templates that can be provided by crew.

Air Canada’s media accessibility objectives, says Lauzon, are to provide accessible content for deaf or hard-of-hearing passengers (including embedded subtitles and dynamic closed captions; to provide a hardware solution for visually-impaired passengers, including a tactile selection audio template on Air Canada’s Thales i4500 and i5000 systems; and to provide a software solution for visually-impaired passengers, including an accessible GUI, audio-cue navigation assistance, and vocal metadata on its Panasonic eX3-equipped fleet, i.e. its B787s.

Improved accessibility for websites and kiosks

The regulatory focus on accommodating passengers with disabilities is not limited to the inside of the aircraft. The process of booking flights and receiving boarding passes today is largely a self-service process, requiring the use of computers and the Internet without the benefit of customer service agents. While new technology may improve the travel experience for hearing, sighted and mobile travelers, they may do the opposite for the deaf, blind or PRM.

Under new US DOT rules announced in November 2013, with an initial effective date of December 12, 2013, airline websites and automated airport kiosks were required to be accessible to passengers with disabilities. The final rule gave airlines 36 months from the December 2013 effective date to begin ordering accessible kiosks, and limited the percentage of kiosks required to be accessible to 25% of all kiosks at any given airport location, with 10,000 or more enplanements per year.

According to the DOT, covered airlines were required to initially make pages of their websites that contain core travel information and services accessible to persons with disabilities, and were given an additional year in which to make all of their web pages accessible.

The standards accepted by the DOT are contained in the widely accepted Website Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and apply, “to US and foreign airlines with websites marketing air transportation to US consumers for travel within, to or from the United States.” WCAG is a technical standard developed through the W3C process, and is an open, technology-neutral standard that can be applied to current and future Web technologies. WCAG 2.0 is approved as an ISO standard: ISO/IEC 40500:2012.

According to the DOT, “the rule also requires ticket agents to disclose and offer web-based discount fares to customers unable to use their sites due to disability… Airlines are already required to provide equivalent services for consumers who are unable to use inaccessible websites. Under the new rule, airlines must also offer equivalent service to passengers with disabilities who are unable to use their websites, even if the websites meet the WCAG accessibility standards.”

Among the constraints for airlines in improving kiosk and Internet accessibility is that hardware and software fragmentation is currently occurring. While the US and several European countries have policies and regulations requiring accessibility, currently each policy has its own, unique set of specifications.

The growing need for accessible self-service travel kiosks caused the leading air travel standards organization, the International Air Transport Association (IATA), to begin considering the effects on a key open industry standard, the Common Use Self-Service Standard (CUSS), which resulted in the airport industry receiving concessions from the DOT in the final rule.

In a 2012 response to the DOT’s original Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) on kiosks, Gary Doernhoefer, general counsel for IATA, commented that, “DOT’s proposal has far too many specifics… I think it is very important that regulation should not specify a technology-based solution,” he said. “The DOT should regulate at a policy level and let the industry work out how best to meet the required standards.” APEX has asked DOT for the same consideration regarding closed captions and descriptive audio.

In a joint memorandum, IATA, Airlines for America (A4A), ACI-North America, the Regional Airline Association, and the Air Carrier Association of America submitted comments highlighting the impracticality of some of the proposed new rules. The result was that the DOT extended the final deadline for airlines to begin ordering accessible kiosks from 60 days following the effective date – which would have been 10 February 2014 – to 36 months or until December 12, 2016.

In addition, the requirement that 100% of kiosks in airports with 10,000 or more annual enplanements had to meet accessibility requirements was reduced to 25%, and airlines were allowed 10 years to reach the 25% accessibility standard.

Doug Lavin, IATA’s regional VP for North America, was among those who lobbied for concessions to the DOT’s rules applicable to kiosks and websites, winning an extension. “Our members recognize the importance of making air travel accessible to all passengers, regardless of disability,” stated Lavin. “Unfortunately, the technology is not yet there [in 2012] to meet the letter of the proposed DOT regulation on kiosks and websites.” Some of the rules were extended into 2016.

The closed caption initiative involves the same issue as the kiosk regulations – the need for regulators to define policy in terms of functional accessibility requirements rather than technical specifications. The original Harkin bill to amend the Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA) to require closed captions in IFE provided that the DOT would take 18 months to draft technical specifications for captioning and then give airlines 180 days to comply.

One of the recommendations by APEX to DOT is to allow the IFE industry to write its own technical specifications through the APEX Technology Committee, and for the DOT to limit its rulemaking to functional accessibility requirements.

A few interesting stories relating to the topic of accessible IFE:

The history of audio description

2000: UK takes the lead with AD Worldwide

2003: Canada introduces mandates for AD

2010: Live AD is pioneered2010: Obama signs the 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act mandating AD on some U.S. Internet content

2015: Netflix introduces AD

2015: ABC in Australia launched AD trial in April; mandates expected soon

APEX’s recommendations to the DOT

1. That any requirements relating to the closed captioning of IFE should apply:

a. Only to newer digital systems which have the capacity to handle closed captioning with a single conversion, and

b. Only to new aircraft for which an IFE system is purchased, and newly purchased systems for any aircraft that currently has a system that is not closed caption capable; there should be no requirement to retrofit existing aircraft with a new system solely to support closed caption capability

2. Only to English language content, and

3. Only to content for which captions have already been created for another market

4. That DOT rules cover only functional requirements, allowing APEX to create its own technical specifications to implement such requirements

5. APEX has also asked that DOT rules limit the availability period during which closed captions are required to be delivered

Closed captions for non-English languages

One of the biggest concerns of airlines outside the USA that fly in and out of the USA with non-English IFE content is the possibility that the DOT will require that those languages be closed captioned, even though many of those languages may not be available with captions. Territory by territory, APEX has limited information on the availability or non-availability of such languages.

For airlines or other affected parties, the National Center for Accessible Media (NCAM) has the resources to do a comprehensive language-by-language and territory-by-territory study that APEX could report to the DOT if such a party were to finance the study. Anyone interested may contact APEX.

Service and ’emotional support’ animals

For airline staff, some of the most difficult matters to deal with involve service animals and ’emotional support animals’ (ESAs) required by passengers.

Under Title II and Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a service animal means any dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for the benefit of an individual with a disability, including a physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual, or other mental disability. A “task” might include pulling a wheelchair, retrieving dropped items, alerting a person to a sound, reminding a person to take medication, or pressing an elevator button, according to the ADA National Network, funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR).

But ADA does not consider emotional support animals (ESAs), comfort animals, and therapy dogs to be “service animals” under Title II and Title III. The principal distinction is that a service animal is specifically trained to perform definable tasks. The Air Carrier Access Act (ACA) permits a passenger to fly with an ESA, but the airline may require that the ESA remain in the passenger’s lap, or under the seat. ACA also entitles the airline to require a letter from a corroborating healthcare professional, but such letters are easily obtainable over the Internet. ACA leaves it to the airline to determine what kind of animals may qualify as an ESA.

Many airlines try to use bulkhead seats for passengers with service animals or ESAs since there may be more floor room and the animal doesn’t have to squeeze under the seat. Airlines believe that many travelers claim that their pets are ESAs simply so that the animal doesn’t have to be stowed below the passenger cabin. An increase in claimed ESAs seems to correspond to destinations where valuable pets are entering dog shows.

But Christmas 2014 in Chicago O’Hare’s Terminal 1 saw United Airlines team with the Lutheran Church Charities’ K-9 ministry to provide a half dozen golden retrievers to greet passengers at the gate. These experienced ‘comfort animals’ had been used after the Sandy Hook shootings, the Boston Marathon bombing, and the severe Oklahoma tornadoes. Now they were relieving passenger stress.

“At Christmas, for a lot of people, it’s a difficult holiday… a stressful time for some travelers,” Tim Hetzner, president of Lutheran Church Charities, told The Huffington Post. “If you’ve ever [flown] out of these terminals, you know the need for stress relief.”

No snakes on planesThe DOT allows airlines to determine which animals may be categorized as ’emotional support animals’ (ESAs) versus ‘service animals’. But the DOT recently offered guidance that snakes should not qualify as ESAs – being the kind of animal that may provide emotional support to one passenger and emotional distress to others. Aside from snakes, the DOT says that the most unusual pet proposed by a passenger as an ESA was a pony. DOT does not recall any requests to categorize unicorns.

Air Canada’s accessibility solutions guided by focus groupsIn order to better determine the needs of visually impaired passengers, Air Canada conducted focus groups. The airline learned that the main kinds of visual impairment are:• Color blindness• Achromatopsia (inability to see color)• Red-green color blindness• Blue-yellow color blindness• Total blindness (complete lack of form and visual light perception)• Low vision

Air Canada learned from respondents in the focus groups that all use technology to assist in their daily lives, with most respondents having a laptop or a reader. Most respondents also have cellphones, but very few used a smartphone.

Air Canada responded to the focus groups in May 2014 with the introduction of the airline’s Boeing 787 Dreamliner, offering a greater selection of movies and TV shows with subtitles or closed captions – both embedded and dynamic – and also offers music albums and playlists, and alternate audio offerings such as audiobooks and podcasts.

Airport accessibility

At the DOT Disabilities Forum in November 2014, at which APEX executive director Russ Lemieux and technology committee chair Michael Childers were invited speakers, one of the most discussed airport accessibility issues involved getting wheelchair assistance when making flight connections. Travelers needing wheelchair assistance are frequently left feeling anxious, not knowing where their wheelchair is and wondering whether it will arrive in time to make the connection. One forum participant recommended an “Uber-type” smartphone app permitting anxious passengers to track the location of their wheelchairs in the airport, just as Uber users track the progress of the taxi en route for pickup.

Blind passengers consider their cellphones as being the best tool for accessing information while inside the airport and would like to see more use of text-to-speech apps.

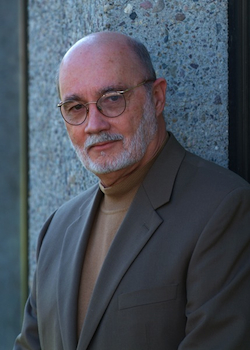

About the author

Michael Childers is a long-time IFE industry consultant. He is a member of the APEX Board of Directors and chairs its Technology Committee. He co-authored APEX’s 2006 response to the DOT’s NPRM on closed captions, and was the principal editor/author of APEX Specification 0403 when it was updated in 2009 to provide for MPEG-4 and bitmap. In June 2014, when closed caption requirements were being added to a Senate appropriations bill, he traveled to Washington DC to work with APEX counsel in drafting documents for distribution on Capitol Hill to show the potential costs of such legislation, and met with Airlines for America and IATA to coordinate the effort.

Michael Childers is a long-time IFE industry consultant. He is a member of the APEX Board of Directors and chairs its Technology Committee. He co-authored APEX’s 2006 response to the DOT’s NPRM on closed captions, and was the principal editor/author of APEX Specification 0403 when it was updated in 2009 to provide for MPEG-4 and bitmap. In June 2014, when closed caption requirements were being added to a Senate appropriations bill, he traveled to Washington DC to work with APEX counsel in drafting documents for distribution on Capitol Hill to show the potential costs of such legislation, and met with Airlines for America and IATA to coordinate the effort.

He has been the editor and co-author of APEX’s documentation for use in engaging the DOT. He was an invited speaker at the DOT’s Forum on Passengers with Disabilities in 2014. In 2013 he co-represented APEX on the FAA PED Aviation Rulemaking Committee along with Rich Salter, CTO at Lumexis.