Researchers at Purdue University in Indiana, USA, having already developed ‘the world’s whitest paint’, as seen in this year’s edition of the Guinness World Records have gone a step further and created a new formulation that is thinner and lighter – ideal for radiating heat away from airplanes, cars and trains. The Purdue team say the paint keeps surfaces so cool that it could reduce the need for air conditioning, thanks to the use of nanoparticles of barium sulphate that reflect 98.1% of sunlight, cooling external surfaces more than 4.5°C below ambient temperature.

The original white paint would make an aircraft look super-clean and eye-catching – ideal for a simple livery such as JAL’s – but as Xiulin Ruan, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering and developer of the paint explained, applying it to such a large surface created a problem: “To achieve this level of radiative cooling below the ambient temperature, we had to apply a layer of paint at least 400 microns (around 0.4mm) thick. That’s fine if you’re painting a robust stationary structure, like the roof of a building. But in applications that have precise size and weight requirements, the paint needs to be thinner and lighter.”

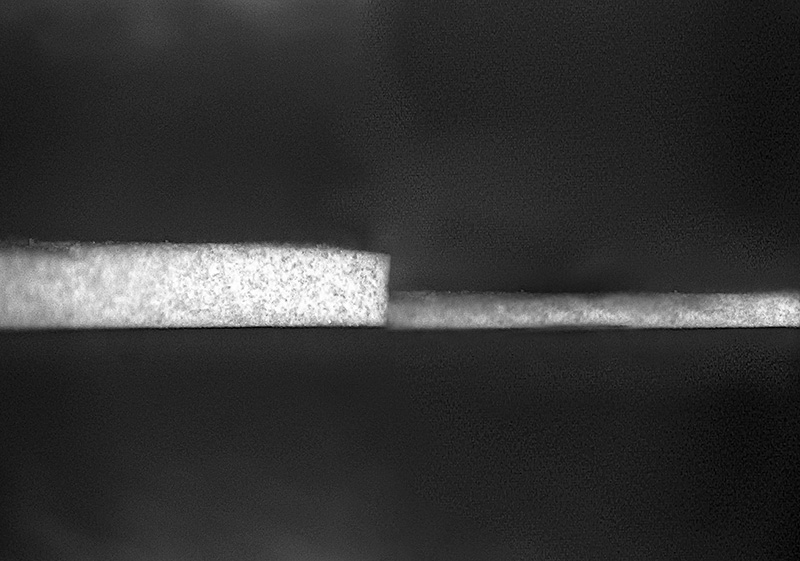

That’s why Ruan’s team began experimenting with other materials, pushing the limit of their capability to scatter sunlight. Their latest formulation is a nanoporous paint incorporating hexagonal boron nitride as the pigment, a substance mostly used in lubricants. This new paint achieves nearly the same benchmark of solar reflectance (97.9%) with just a single 150-micron (0.15mm) layer of paint.

“Hexagonal boron nitride has a high refractive index, which leads to strong scattering of sunlight,” said Andrea Felicelli, a Purdue PhD student in mechanical engineering who worked on the project. “The particles of this material also have a unique morphology, which we call nanoplatelets.”

Ioanna Katsamba,, another PhD student in mechanical engineering at Purdue, ran computer simulations to understand if the nanoplatelet morphology offers any benefits added,. “The models showed us that the nanoplatelets are more effective in bouncing back the solar radiation than spherical nanoparticles used in previous cooling paints.”

The paint also incorporates voids of air, which make it highly porous on a nanoscale. This lower density, together with the thinness, provides another huge benefit: reduced weight. According to the Purdue team the newer paint weighs 80% less than barium sulphate paint, yet achieves nearly identical solar reflectance.

“This light weight opens the doors to all kinds of applications,” said George Chiu, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering and an expert in inkjet printing. “Now this paint has the potential to cool the exteriors of airplanes, cars or trains. An airplane sitting on the tarmac on a hot summer day won’t have to run its air conditioning as hard to cool the inside, saving large amounts of energy. Spacecraft also have to be as light as possible, and this paint can be a part of that.”

This sounds good, but can aircraft operators buy the paint? Xiulin Ruan explained, “We are in discussions right now to commercialise it. There are still a few issues that need to be addressed, but progress is being made.”

Either way, these Purdue researchers look forward to what the paint could accomplish. “Using this paint will help cool surfaces and greatly reduce the need for air conditioning,” Ruan added. “This not only saves money, but it reduces energy usage, which in turn reduces greenhouse gas emissions. And unlike other cooling methods, this paint radiates all the heat into deep space, which also directly cools down our planet. It’s pretty amazing that a paint can do all that.”

Patent applications for this paint formulation have been filed through the Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization. The research was performed at Purdue’s FLEX Lab, Ray W. Herrick Laboratories and Birck Nanotechnology Center facilities.