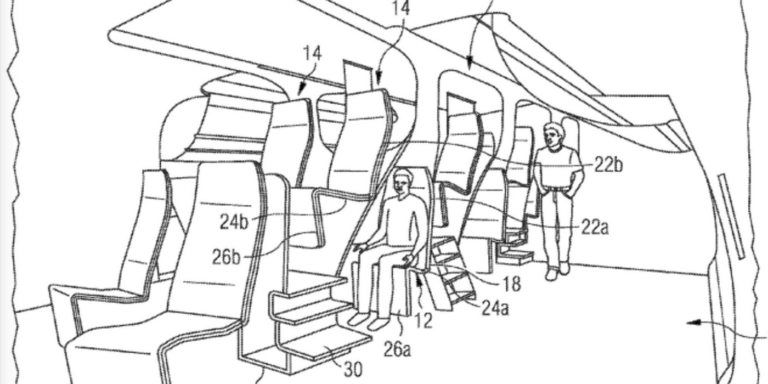

Airbus files around 600 patents each year, but one in particular made international news in 2015, sending news site comments sections into meltdown as the public swore it was the last straw in cramped travel conditions. Outraged comments ranged from oaths never to fly again if the design became reality, to comparisons with sardine cans, and even 19th century slave ships. The cause of the uproar? A patent application for a double-deck business class cabin.

The idea of monetizing the vertical space in the cabin is something every major airframer, airline, design house and seating manufacturer has explored at some point, but clearly no such ideas have been implemented in recent years. Is it that the market isn’t ready for a second tier of seating, or is the idea simply not viable in the real world?

“Innovating with LOPAs in the traditional way is becoming more difficult with every new patent that is published. The landscape of IP is growing ever denser, and this makes the third [vertical] dimension very appealing and indeed interesting,” says Anthony Harcup, an associate at the Acumen transport design consultancy.

Harcup adds that if vertical cabin space is to be used, careful consideration must be given to whether people will be prepared to embrace a travel experience that offers different benefits and drawbacks to today’s norm.

“When you deviate from an offer that passengers have come to accept as standard, you have to tread very carefully,” he warns. “As history has shown, it takes a brave airline to put its best foot forward and make a leap of faith. With the right idea and a strong team, it is these kind of ventures that make history. Get it wrong and you are in trouble.”

Let’s explore some expert opinions to assess the risk and reward of creating an additional level of seating.

Cabin density

If the aim of adding a second seating level is to increase cabin density, would it really work? After all, while the upper tier gives an opportunity to add more seats, you may lose some of that benefit as lower-level seats are removed in order to provide a means to access that space.

Martin Darbyshire, CEO of the Tangerine studio, has considered the practicalities of accessing the upper tier: “The interesting twist is that because you have to create things like an additional aisle and some other access aspects, you don’t get a massive increase in the number of seats, which I think quite quickly calls into question the validity of this sort of direction – particularly as you probably can’t do this kind of thing adjacent to the windows in a relevant and appropriate way.”

However, if using the vertical space isn’t considered as a mere ‘pack ‘em in’ exercise, it begins to make a little more sense. “Is this really just about adding seats? No, I think it is about whether you can actually change the degree to which somebody can recline and offer greater comfort in a reclined position, but still maintain a reasonable level of cabin density,” adds Darbyshire.

However, Adam White, a director at Factorydesign, has a little more confidence in the passenger density potential of mezzanine seating. “The only reason anyone in the industry would pursue the idea is to get higher cabin density. That’s my, perhaps cynical, observation, and I think that [a second tier] would add seats if that were your only ambition,” he says. “But I think from that higher density, increased privacy and a reduced cattle herd feeling could be achieved with the second level.”

Ben Orson, managing director of JPA Design, adds, “Railcar solutions that do this efficiently have existed for a long time. The overall density benefit could far outweigh the small reduction in seating from adding a set of steps. A cleverly designed pod could be a great place to spend time. We need to think about the overall experience. If the freed-up space allows for another benefit, then the overall situation could be much improved.”

Certification concerns

Mezzanine seating seems to have potential in terms of cabin capacity and human comfort, but how does it stack up in terms of meeting aviation requirements? Would the added weight and stress created by a second level make it through the certification process?

“The biggest challenge is neither the design nor the engineering. It is the certification,” warns White. He states that there would be “an awful lot of leverage” going through the floor, but that by fixing the seating to both seat tracks and ceiling attachment points, it could work.

“I can’t imagine that current certification allows for such a design,” he adds. “However, over the past five years we have seen more and more innovation in cabin design, and my experience of the certification bodies is that if an intelligent plan is put in front of them, then they are very prepared to listen.”

Acumen’s Harcup is less confident, though. “On a practical level, stacking and tessellating real people in seats that must pass dynamic certification testing is no mean feat. With only seat tracks available to secure assemblies, which could potentially be quite high up in order to be effective, a number of engineering conundrums create a seemingly impossible set of challenges. It is likely that this is why there is yet to be an effective solution on the market.”

Harcup has a similar view to White, saying that the effective use of vertical space for passenger seating depends on closer collaboration with the airframers to provide ‘flex-zones’ where upper attachments are possible – enabling the construction of floor-to-ceiling structures that are certifiable. “This could unlock a whole new generation of design thinking,” he states.

The basic idea of stacking composite pods on top of another, attached to conventional seat tracks, has been explored extensively by Tangerine. In the case of Tangerine’s Club Limo concept, it was envisioned that the two levels of seating would be attached to the existing seat tracks, with no other hard fixings required. However, Darbyshire is also of the opinion that it may be possible to attach an upper deck to other points in the airframe.

“But you are definitely going into unknown territory to some degree and it’s potentially going to call into question the way the dynamic tests are currently carried out,” he cautions. “Therefore you are going to have to allow quite a lot of development time if you are going to take risk out of the program.

Stepping up

Another major practical issue of adding an upper level is that of access and egress. Steps will clearly be a bar to access for some passengers with limited mobility, and they may create potential issues for the 90-second evacuation requirement.

“There are very real challenges along these lines, which have prevented many ‘stacked’ passenger seating solutions from being commercially viable,” states Harcup.

Acumen has a yardstick for assessing cabin concepts, which in an industry that loves technical terms and acronyms, is the charmingly low-tech ‘granny test’. If Harcup feels that his grandmother wouldn’t be able to get into or out of a passenger enclosure without discomfort, then he feels its design is likely to discount a large volume of the market. “Solutions involving the vertical space must carefully navigate and compensate this issue”, he says.

Clearly any upper aisle would have to be wide enough to meet the general aviation requirements, but Darbyshire adds that if steps are used, they would have to be wide enough for two people to pass at the same time. “But I think it is doable,” he says. “There is nothing in the idea that absolutely scares the pants off me.”

Breathing space

Another practical consideration is that as the center overhead stowages are removed, the center PSUs go with them. Lighting and crew call buttons are not difficult to relocate, but oxygen masks present a bigger problem, for both lower- and upper-level guests sitting along the centerline of the cabin.

Chemical oxygen generators could be fitted into the center seats, but they are not a lightweight solution. Darbyshire instead proposes reconfiguring the current gaseous manifold systems into a different location that can be accessed by both levels of passengers.

A confident White adds, “As a designer, my position with innovation is always one of optimism. I like to imagine that between the engineering force of the airframer and us developing it, there would be the wit to overcome such obstacles.”

Economy application

From the views given by these cabin design experts, it seems that business class cabins could benefit from a second level of seating – and that it is not an entirely implausible idea. But what of economy class, where the potential cabin density benefits of tiered seating would be of great interest? Many of the outraged comments about the Airbus patent seemed to mistake the concept for an economy cabin idea, but are their concerns unfounded?

“Well I like it,” White says of the idea of stacked seats in economy cabins. “I like the fact that it doesn’t say ‘one seat fits all’, which is the bane of economy class. It allows for the fact that there are some people fit enough to climb up a couple of steps and who, I have no doubt, are prepared to do so to enjoy the solitude. I love the idea of being able to climb into essentially my own space. From that point of view, I think it is brilliant.”

The notion of economy cabins having more choice and being more, well, interesting than the usual rows of identical seats is compelling. “The economy cabin has a lot of different people traveling for different reasons, and it is only for convenience that everything is pretty much the same unless you are in an emergency aisle or the front row,” says White. “I think what is most exciting about the Airbus patent is that a proposal from one of the world’s big players could shake up the rank and file of economy class seat design.”

However, Orson warns that in some cultures the idea of having someone sitting above is not appealing, and that customer demand for upper and lower seats would have to be carefully considered before committing. He adds that perhaps the upper seats could attract a premium.

But in the high-density environment of an economy class cabin, wouldn’t adding an overhead mezzanine level make the space feel rather claustrophobic for lower-level passengers? “I think as long as it is done with care and designed sensitively, there could be a much more intimate feeling,” says White. “I hesitate to say a private jet feel because it is not, but the feeling of having a much more exclusive experience than being in the sort of auditorium seating that we have today.”

For those wanting space, with the double deck running along the centerline of the cabin, the outer rows would still offer a more spacious feeling – and perhaps the window seats could also attract a premium.

Our panel of designers seem confident in the potential of the concept of tiered seating. Whether we will see it fly or not, it is interesting to see an exploration of new ways of integrating seating with the airframe for potential airline and passenger benefit. The space may be finite, but why should the way it is used be finite?

Bonus content: Here’s what else the contributors had to say…

Looking at the Airbus patent itself, we asked Martin Darbyshire, CEO of Tangerine, for his view of the concept

“I think there is a whole central set of disadvantages to it that really call into question whether it is a sensible thing to do. Do the benefits outweigh the disadvantages? I’m not sure they do. It is certainly inventive, interesting and different, but is it good enough? I think the answer is no.

“I think some of the thinking in it is actually quite interesting and quite powerful. I think there are aspects of it that are very questionable, but then again it depends on what Airbus’s strategy is, and we don’t know what its strategy is.

“We have got a good idea of what Airbus is trying to protect within the patent. Viewing it from the perspective of what IP lawyers call a ‘person who is skilled in the art’, I might say, ‘Yes there are novelties in there. There are original bits’. But I also might look at it and say, ’Are they deliverable? Can you overcome the issues that it may present?’

“My gut feeling is I don’t see a lot of point in it to be perfectly honest. Because I don’t see how it is going to radically develop much higher levels of density. For every one little step-up space, you are going to lose a seat. Are you getting two seats back? The answer is no, so what are you really getting?”

Premium economy?

Do our panel see potential in the premium economy cabin? Perhaps a second level would work well in premium economy, or even as a hybrid cabin with economy on the lower level and premium passengers having a slightly more luxurious and personal experience above.

“I think premium economy is an interesting one to watch because it has evolved in a lot of different ways in terms of what you might get, but ultimately they all tend to be a bigger seat with more room and more recline,” says Adam White of Factorydesign. “This is a different environmental experience. I think that is one of the things I particularly like about it.”

Tangerine’s Martin Darbyshire adds, “I guess if it opens up a much more reclined posture in economy, then that could be a route. If you are not trying to add more seats, but just trying to redistribute the available space and offer a more comfortable solution, then I guess it is a possibility.”

Factorydesign has already experimented with stacked seating, with its Air Lair concept:

Factorydesign was challenged to create a fantasy concept for Contour (now Zodiac Seats UK), and devised the striking Air Lair design, which was a double-deck system of individual pods, claiming to offer 30% additional passenger accommodation in the same footprint as a single-deck layout. The concept lay somewhere between premium economy and business class.

“We did have a weather eye on creating something that had a basic intelligence about what it was suggesting a cabin could do in terms of new innovation,” explains Adam White, director of the studio. “What we were trying to say was that thinking about the cabin in layers was important.”

The concept had a very mixed reaction at its reveal at Aircraft Interiors Expo 2012, but White has noticed a recent increase in people approaching him to talk about the validity of Air Lair as an idea, as more people are seeking new ways to optimize cabin space.

Perhaps the concept was just a little ahead of its time. “That would be our ultimate wish. That people are able to look back at Air Lair in a few years and say, ‘That was the first moment I thought that what we have launched today was possible’.”

See here for a video of Adam White explaining the design

Service aspects

It seems an upper level of seating is possible in terms of engineering, but one of the biggest problems could lie in the service aspect. No top-tier airline will want its service standards to decline as a result of a redesigned cabin.

“Perhaps when you have innovated to this level with seating you have to re-examine how to innovate with catering,” states Adam White of Factorydesign. “As the seating products and indeed the service style has become much more sophisticated in the premium cabins, aircraft trolleys have disappeared from those classes with a lot of carriers. While the sheer volume of meals required in economy means a delivery system is required. I think at this moment it is a blank sheet of paper, although the standard equipment on an aircraft would need to relate to the design in some respect.”

Ben Orson of JPA Design has an idea: “It is conceivable that a new model of service would need to be developed alongside the seat that would address this. For the majority of an aircraft’s passengers in economy, the reduced expectation might make this challenge easy to overcome. The new design might enable ideas such as onboard central restaurants to be implemented.”

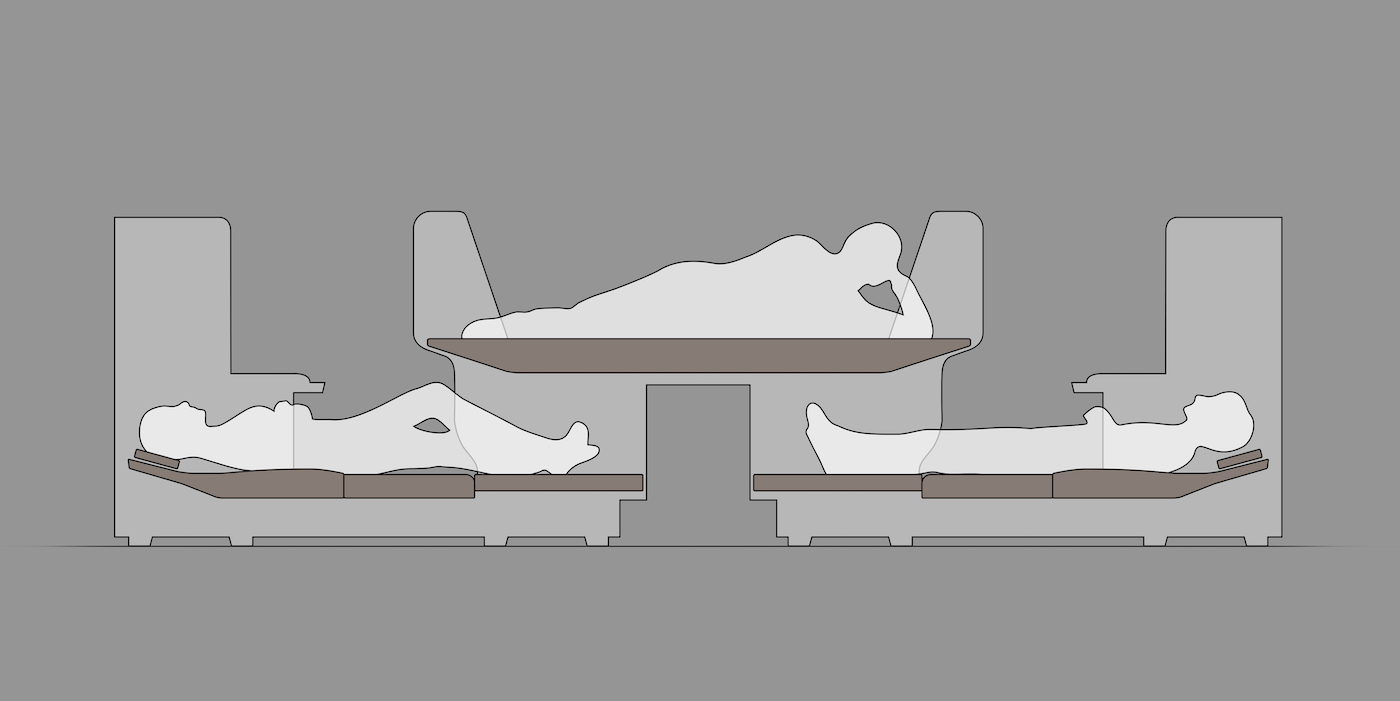

Clever Formation

In the mid 2000s, Robert Henshaw, a partner at Formation, noticed that wide-body aircraft cabins were generally becoming taller, and began thinking about the possibility of using some of this space to layer the bed and seat arrangements, creating higher passenger density without compromising passenger living space.

Henshaw has created a few layered seating concepts, the latest featuring an arrangement of two forward-facing and two aft-facing lie-flat seats, which are separated by a raised premium class suite with living space comparable to a first class suite at a pitch of 80in or more. The standard business class seats that bookend the suite underlap the armrest areas of the suite, and when the suite converts to a bedroom, the bed overlaps the armrest and thus the lower leg area of the four bookending seats.

The lower positioning of the bed provides two advantages. The first is more vertical space in the footwell to better accommodate crossed legs, while the second advantage is improved step-over egress for the window or center seats.

The concept is well suited to several aircraft types. The high-density 1-2-1 suite and 2-4-2 standard lie-flat arrangement is suitable for the A350, A380 main deck and B777. A more spacious but less dense arrangement of 1-1-1 and 2-2-2 would work well for the A330, A380 upper deck, and B787. For single aisle, a 1-1 suite and 2-2 standard lie-flat arrangement would be a very compelling transcon product offering.

In a 2-4-2 B777, Formation claims that an overall seat gain of 17 lie-flats is achieved, compared with a typical staggered or herringbone LOPA. The cabin is comprised of 46 standard lie-flats and 11 premium suites. According to the studio, the ability to offer 11 premium suites and still have a higher count of standard lie-flat seats could be a game changer.

Flex appeal?

As part of an airline pitch, Tangerine developed the Flex concept, which gives window seat passengers a separate bunk located above the inner seats. The two spaces are entirely separate, giving window seat customers a comfortable reclining seat for TTOL, working, dining or watching films, and a separate, dedicated and private sleeping area across the aisle and up five steps.

“From a customer proposition point of view it’s really powerful,” states Martin Darbyshire of Tangerine.

While the inner passengers do not have access to the mezzanine-level bunks, their seats do convert into lie-flat beds. The concept sketches show the inner seats facing sideways in the cabin, but that is not a necessity for the arrangement to work, so long as there is sufficient space for the center seats to be converted into flat beds.

There is clearly a big disparity in the passenger offer for window and center occupants, which would have to be addressed in the ticket pricing. However, the concept does have a big drawback…

“The scary thing is that the number of seats that you get is not bigger than using a current lie-flat solution in a fairly dense form,” states Darbyshire. “I think that is really going to call into question the validity of the concept for a lot of airlines.”