Air traffic is a growth market. Worldwide, the number of air passengers is increasing by about 5% a year, and global demand is doubling every 15 years. This solid rise in passenger volume is not the only force behind the dynamism in the aviation business. Another factor is a related demand for aircraft that are more efficient and more economical to operate. This study by Porsche Consulting, which surveyed top managers at manufacturing, supply, and logistics companies, clearly shows that there is considerable potential in the aviation industry that has thus far not been utilised. One quarter of the companies questioned, for example, could increase their productivity by more than 30% by means of better coordination with their supply chains. The study also shows that the industry could save around US$42 billion by 2030 over today’s production costs if it optimizes its value chain.

Air traffic is a growth market. Worldwide, the number of air passengers is increasing by about 5% a year, and global demand is doubling every 15 years. This solid rise in passenger volume is not the only force behind the dynamism in the aviation business. Another factor is a related demand for aircraft that are more efficient and more economical to operate. This study by Porsche Consulting, which surveyed top managers at manufacturing, supply, and logistics companies, clearly shows that there is considerable potential in the aviation industry that has thus far not been utilised. One quarter of the companies questioned, for example, could increase their productivity by more than 30% by means of better coordination with their supply chains. The study also shows that the industry could save around US$42 billion by 2030 over today’s production costs if it optimizes its value chain.

Improving production processes and value chains thus becomes the crucial prerequisite for ensuring profitability and higher delivery rates. This study shows that in order to increase delivery ability and capacity, the focus has to be placed on improving coordination of the supply chain between aircraft manufacturers and their first, second, and third-tier suppliers. The aim is ‘to grow without growing,’ i.e. to increase production in an investment-neutral way without expanding infrastructure. To do so, the interplay among all those involved has to be critically examined. “The New Value Chain” therefore focuses on improving planning and scheduling in both production and the supply chain. Three factors are especially important here:

• Creating more transparency by standardising communications

Greater transparency regarding processes, dependencies, and available capacities generates a better understanding of the supply chain’s potential for performance. The prerequisite here is the provision of up-to-date information at all times to all involved.

• Increasing planning quality by specifying and adhering to production planning and manufacturing sequences (‘frozen zone’)

Better planning quality refers to the agreement between planned and actual states, in order to show current performance capacity and provide the requisite information to all partners. The only way to harmonise the entire supply chain is to communicate needs in a long-term, stable manner.

• Achieving greater professionalism through a new understanding of roles

All those involved need to understand and master their new roles in order to respond in a sufficiently flexible manner to short-term influences on the market. Another important factor here is to define shared systems of aims within the chain.

Market demands will change by 2020. The partners in the value chain need to adjust to the new conditions. This study shows that their current roles and responsibilities are changing accordingly as part of “The New Value Chain”. Every member of the chain will be taking on supplementary tasks on a partner-oriented basis, tasks that are mutually adjusted as perfectly as possible. First and foremost, responsibility for controlling this network will be shifted significantly. This will no longer be exclusively the main task of aircraft manufacturers. Instead, first-tier suppliers will assume considerably more responsibility for systems. They will be turning into major control centers and serving as links between aircraft manufacturers and the other suppliers.

The aircraft manufacturers, by contrast, will become systems architects and integrators, and set the tone within the value chain. Development remains their most important expertise, and responsibility for planning and coordination remains completely in their hands. Implementation, however, will be delegated to the suppliers. For this to happen, it will be necessary to provide stable forecasts along the supply chain and ensure a constant exchange of information. Logistics service providers are developing into an innovative interface within the value chain, and providing stimuli for optimising the supply chain’s logistics.

Market environment and challenges for the aviation industry

Market environment and challenges for the aviation industry

“The biggest aircraft contract in history” – superlatives of this sort are regularly announced by news outlets. These might be Boeing’s 777-X types and 737 MAX or the new Airbus A350 XWB or A320 neo-family, all of which enable airlines to considerably increase fuel efficiency and are therefore bestsellers on the market. Their makers vie with each other to publicise these mega-orders.

The aviation industry is a growth market: VietJetAir recently made a stir at the Singapore Air Show 2014 with an order of more than 100 aircraft of the Airbus A320 family, for example, and Emirates made headlines by ordering 150 Boeing 777Xs and 50 Airbus A380s for a combined value of nearly US$100 billion. Growth in the industry is historically substantiated, as well as anticipated in the market outlooks of the major manufacturers for the coming two decades.

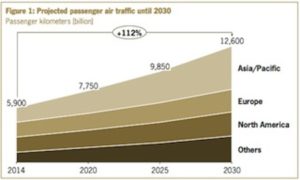

World air traffic is growing by around 5% a year. General economic growth is the major driving force here, among other reasons because it is fuelling a strong increase in the proportions of affluent middle classes in newly industrialised countries. This in turn is driving the demand for air travel in the tourism industry, and is also promoting business air travel as a result of greater international networking. According to the latest estimates, worldwide air travel in passenger kilometers is expected to more than double from 5,900 billion in 2014 to a good 12,600 billion in 2030. This will be accompanied by further strong growth in the market for aircraft, driven in large part by two factors: Demand for air travel in emerging markets is increasing rapidly; and cost pressures are building enormously on airlines and forcing them to invest in more efficient, modern fleets at an earlier point than in previous renewal cycles.

Demand for cost-efficient aircraft

Rising passenger numbers are not the only driving force behind the economic dynamism of the aviation industry, however. A good 40% of market volume until 2030 will be based on demand for new aircraft that can be operated at lower cost. As Ray Connor, president of Boeing Commercial Aircraft, put it in the company’s latest outlook for 2013-2032: “The products that provide the most efficiency will continue to be the products of choice.”

The demand for more effective aircraft is influenced in large part by the fact that fuel accounts for a high share of airline operating costs. This share has doubled over the past 10 years, and now makes up nearly half of overall costs. Although jet aircraft are generally designed for a lifespan of more than 30 years, the fuel-efficiency factor has been leading to what can be a considerably shorter period of time in the portfolio of major airlines. Lufthansa, for example, will be replacing the Airbus A340 fleet it acquired as of 1993 with the new A350 starting in 2016. Emirates Airlines is currently removing the first jets from its A340-500 fleet, which is only 10 years old. Replacing these aircraft is enabling fuel costs to be reduced by up to 25%, which means that a single long-distance jet can save an average of more than US$3 million a year. This is all the more significant given that airlines cannot pass on the full extent of higher fuel prices to their customers on account of the strong competition they face, but rather have to offset them by cutting costs.

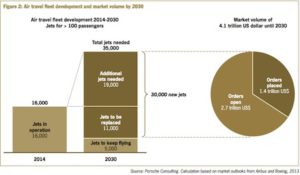

The growth in air travel and the need for more efficient jets is generating demand for a good 30,000 new jets in the segment for 100+ seats. As such, the total fleet will more than double to around 35,000 by 2030. This outlook is very positive for the aviation industry, for if each jet entails an average investment of US$137 million, that means a corresponding market volume of US$4.1 trillion in payable investment.

Around one-third of this volume has already been allocated to the Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier, Embraer, and Comac manufacturers in the form of orders and options. But orders for 20,000 jet aircraft at an estimated value of US$2.7 trillion are yet to be placed.

At the same time, however, this positive starting situation on the market side is posing ever greater challenges to the industry. There is much to be done in terms of on-time delivery of orders, for even today only 80% of aircraft are delivered to customers by the dates agreed upon. For new projects, delays will even be measured in years.

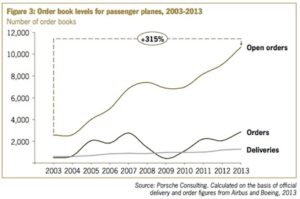

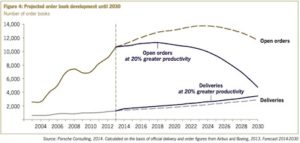

The overall number of deliveries – the rate, i.e. the number of deliveries per unit of time – urgently needs to be raised. For the number of orders is increasing considerably faster than the delivery rates. The number of orders over the past 10 years has risen by an average of 6.5%, while deliveries over the same period of time have risen by only 4.7%. The backlog over this period of time has increased by more than 300%. Even if the planned increase in delivery rate is taken into account, current unfilled orders of approximately 10,000 aircraft already represent a production volume of a good seven years. And the gap between orders and deliveries will grow all the more.

To handle both existing and future volumes of work, the aviation industry has to increase its efficiency and production to a thus far unprecedented degree. The performance of the entire supply chain in the aviation industry has to be considerably increased.

The aim: Performance and profitability

The ability to actually deliver the number of aircraft ordered by the date agreed upon is a decisive competitive factor in the industry. The results of the study clearly show this. Not only delivery figures offer potential for improvement, but also profitability, which has the highest priority for all participants in the market. For although the number of larger aircraft in the civilian market is manageable, the average profit margin of around 6.5% is comparatively low compared to the target figure of 10%. In the future, competition at least in the sector for jets of up to 160 seats will become tougher because new providers are entering the market. While average margins in the supplier sector are higher at 11.5%, this does not apply to the overall industry. The intensity of competition depends on each individual product sector, as well as on the provider’s degree of specialisation and level of technology.

The results of this study show that even industry leaders themselves do not see the most urgent challenges in market-oriented issues such as acquiring new sales markets, increasing market shares, or offering new products, technologies, and services. In light of market forecasts, these views are not surprising. At the same time, the survey results provide a very nuanced view of the industry’s focal topics over the coming years. From the perspective of the industry, the key prerequisite for ensuring profitability and delivery rates lies in optimising production processes and value chains.

Price pressure is not the solution

According to many reports in the press over recent months, aircraft makers are seeking to negotiate prices with their suppliers in an effort to reduce costs. In the view of Porsche Consulting, however, talk of general price pressure on suppliers in the aviation industry falls short. A more nuanced account is needed. High-tech suppliers with top-level technology enjoy the best protection against this proclaimed cost pressure, because there are no alternatives to them, cheaper or otherwise. “Standard” suppliers – whose products are also provided by other makers – are more vulnerable to price pressure because they offer no unique products, so orders can be shifted to other suppliers in their sector at least over the medium term. Here, however, it should be noted that legal regulations in the aviation field in the form of authorisations and certifications can also make such shifts difficult and weaken the negotiating positions of aircraft manufacturers. The third category consists of suppliers that have a certain monopoly position but are nevertheless in difficult financial straits. Here too there is little room for negotiating prices. Clearly, profit margins cannot be increased solely by reducing the prices paid for components from suppliers. The major contribution here has to come by other means.

According to the results of this study, costs can best be reduced over the short to medium term by increasing production efficiency and by optimising the supply chain. And this is true virtually regardless of the degree of dependence between manufacturer and supplier, because savings achieved by any member of the chain can be shared. This has been shown not only by experience from the Porsche company, but also by project experience gained by Porsche Consulting in the aviation and aeronautics industry.

Despite the challenges currently associated with delivery rates and profitability, we can conclude that the starting situation for the industry overall is very positive. The high and secure demand and the resulting potential for growth offer a large number of opportunities for all participants in the market. Porsche Consulting has developed solutions for production and the value chain, which are subsumed under the idea of “The New Value Chain”. The focus here is on optimising the supply chain between aircraft manufacturers and suppliers.

“The New Value Chain” for aviation

Given the continuing high level of incoming orders for larger passenger jets and the existing backlog of more than 10,000 orders, the main aim of the aviation industry is to ensure constant delivery rates. This aim can be achieved by using the existing resources in the industry if these resources are put to better use – via comprehensive planning and scheduling mechanisms along the entire value chain. This is the key to both profitable and sustainable growth.

The main insight of this study is that attention must be directed to optimising the supply chain between aircraft manufacturers and their suppliers of the first, second, and third tiers in order to increase delivery performance and capacity. The main prerequisites here are greater clarity in the classification and graduation of responsibilities on individual levels, better coordination processes, and comprehensive planning. It is not a desirable alternative to set up additional production capacities, because this is excessively cost-intensive as well as prohibitive in terms of securing profit margins. According to the philosophy of Porsche Consulting, it should only be considered as an extreme means or final option. Other solutions first need to be employed, which lead more quickly and easily to success.

Porsche as an example

Growth without growing – or in other words, growth while largely abstaining from expanding infrastructure with the associated investments – has to be the aim. There are various analogies for this in technological development, such as in the automotive industry where innovative engines can generate greater levels of output with smaller displacements. For example, production capacities can be increased solely on the basis of improving the interplay of all those involved. The sports car maker Porsche has shown this in impressive form: over the past 20 years it has increased its production volume ten-fold while at the same time reducing the production time for e.g. a Porsche 911 by 74%. Its robust supply chain displays an impressive inventory holding period of less than one day and a production stability of 98%. The company’s aim of raising productivity by 6% a year means that it works together on a partnership basis with its suppliers to increase performance of the overall system anew every year.

Here is where ‘The New Value Chain’ from Porsche Consulting comes in: it focuses on planning and scheduling of both production and the supply chain. The approach is based on the principles of operational excellence and a lean company. It concentrates on the value-added process in production, orienting processes clearly towards customers, and minimising stockpiled, unproductive inventory. The value chain represents an aviation-specific approach to the interplay of all members of the value chain, and is the result of the expertise gained by experts from Porsche Consulting over a large number of projects in practice.

Potential and opportunities

Potential and opportunities

This study is based on a wide-ranging survey of views in the aviation industry, the first of its kind on this subject. Porsche Consulting questioned more than 80 high-ranking managers at aircraft manufacturing, supply and logistics companies in Europe, the USA, Russia and Asia in primarily individual interviews. The crucial result: through comprehensive planning of the value chain, the approach taken by ‘The New Value Chain’ offers the chance to generate investment-neutral growth and increase delivery rates and performance. This is the only way to reduce the backlog of orders. This value chain can thus make a key contribution to ensuring and increasing profitability in the aviation industry. It generates stability in the processes. This enables an increase in efficiency, which in turn lowers costs and increases both production volumes and on-time deliveries.

The goal: Delivery reliability down to the day

Delivery reliability can be improved by an average of 15%. For a good fifth of the companies surveyed, this potential lies at 30% or more. Thus far the industry has had an average on-time delivery rate of only around 80%. Even the best companies hardly achieve more than 90%, and this although the standards for on-time delivery in aviation and aeronautics are usually more generous than in the automotive industry, for example. Deliveries are often still considered on-time when they arrive up to five days before or two days after the date agreed upon, i.e. within a period of seven days. The goal should be delivery down to the day at least, and that for more than 95% of deliveries in the chain.

Optimizing the supply chain has an average industry-wide potential of increasing hourly productivity by 20%. A quarter of the companies could even increase their productivity by more than 30% if they improve the coordination of their supply chain. Based on a reduction of 20% in production hours, the results of this study reveal potential savings of US$1.4 million for the production of just one single-aisle aircraft. By optimising its value chain to handle current and anticipated orders up to 2030, the aviation industry could save around US$42 billion over its current means of production. Throughput times would decrease as well. The resources saved by this increase in productivity could be put into raising delivery rates.

Shorter throughput times would lead to a reduction in capital costs of US$25,000 per aircraft per day. Additional optimisation measures can follow as well. The example of Porsche shows that continuous improvement is possible even at a high level over a long period of time. Porsche has succeeded in increasing its productivity over the past 20 years by 6% a year, and reducing the production time for a Porsche 911 by a total of 74%.

Greater productivity and lower inventory levels need not conflict

Not only the responses from the participating top managers but also Porsche Consulting’s own project experience show that inventory levels need not be increased in order to raise productivity. The study results demonstrate that reliable and stable production planning can reduce inventory levels of raw materials and semi-finished items by 25%, and levels of finished items by a not insignificant 15%. This estimate has proven to be realistic as shown by numerous project results from Porsche Consulting in the aviation industry.

Not only the responses from the participating top managers but also Porsche Consulting’s own project experience show that inventory levels need not be increased in order to raise productivity. The study results demonstrate that reliable and stable production planning can reduce inventory levels of raw materials and semi-finished items by 25%, and levels of finished items by a not insignificant 15%. This estimate has proven to be realistic as shown by numerous project results from Porsche Consulting in the aviation industry.

The comprehensive approach of ‘The New Value Chain’ focuses on the relevant leverage mechanisms. The chain thus enables higher delivery rates in the industry without the need for additional capacities or resources. Companies that orient their strategies toward comprehensive cooperation along the value chain will benefit disproportionately from the anticipated growth in the industry while at the same reducing their costs.

The approach of ‘The New Value Chain’

Porsche Consulting’s evaluation of the survey it performed showed that three key elements of ‘The New Value Chain’ are needed to meet the aim of profitable growth: greater transparency, higher planning quality, and greater industry professionalism overall by the partners involved. Analyses of the core indices of productivity, capital tie-up, and delivery reliability show that companies that are already paying greater attention to these elements come out significantly ahead of companies that neglect them.

Creating transparency

Greater transparency among members of the supply chain with respect to processes, dependencies, and available capacities creates a better understanding of the supply chain’s ability to perform. But it is also clear that major deficits still remain in this area, as reported by a first-tier supplier: “Informational gaps arise in the segmentation [of communication] from suppliers to their component producers.” Important content is lost in the dissemination of information to more subordinate levels of the supplier chain. At present these companies are not able to further process information in a professional and standardised manner, although this will be one of the main tasks for suppliers in systems production.

At 67% of the companies surveyed, the majority of different communications media – including fax, phone, e-mail, supplier portals, and ERP systems – currently require considerable additional time and resources. Existing deficits mean that companies often (71%) do not know the extent of actual customer demand, that a manual, non-systemised ordering system is run in parallel, and that non-uniform, prioritised interjection of short-term orders are customary. For companies without uniform data exchange, these factors exert nearly one-third higher negative influence on production and frequently lead, for example, to the need to change order priorities.

At 67% of the companies surveyed, the majority of different communications media – including fax, phone, e-mail, supplier portals, and ERP systems – currently require considerable additional time and resources. Existing deficits mean that companies often (71%) do not know the extent of actual customer demand, that a manual, non-systemised ordering system is run in parallel, and that non-uniform, prioritised interjection of short-term orders are customary. For companies without uniform data exchange, these factors exert nearly one-third higher negative influence on production and frequently lead, for example, to the need to change order priorities.

Communications as a key factor

Comparative analysis of the two groups also revealed that companies with more established communications standards have 70% knowledge of the production capacities of their suppliers. The other group achieved a figure of only 19% here. This exerts a strong effect on delivery reliability. The leaders here achieve values of 90%, whereas those with less standardised communications achieve a mere 80%. A clear connection is evident: the more a company knows about its own abilities and those of its suppliers, and the more it is able to communicate this knowledge in a clear and standardised way both internally and externally, the more efficient its supply and production processes will be. That starts with the respective company itself, of course. As a supplier put it in the survey, “Internal transparency is needed to ensure on-time delivery.”

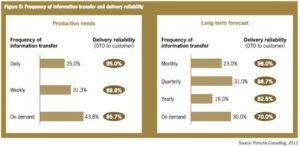

Transparency is also influenced by the frequency of data transfer. However, this aspect of communications in the aviation industry’s supply chain currently appears to be at a below-average level compared to that in the automotive industry. Just 23% of the companies surveyed receive monthly long-term forecasts from their customers, and nearly half of the companies receive such forecasts only on a quarterly basis or even less often. The study clearly shows that companies that receive long-term forecasts from their customers monthly or at least quarterly achieve considerably better on-time delivery levels to their customers.

One-third of the companies convey even their short-term needs on only a weekly basis. This is a source of potential, because more frequent and standardised data transfer has positive effects that are clearly measureable. These positive effects apply on the one hand to punctuality by the respective suppliers who can adapt better to the production programme because they are “closer” to their customer’s planning. And the company’s own punctuality also increases because customer needs become more transparent and the two sides both have the same state of information. Suppliers who receive information on customers’ needs on a daily basis have an average on-time delivery rate to their customers of 95% compared to only 88.8% for weekly information.

In conclusion, one should note that the quality of planning and forecasting rise noticeably with the degree of standardisation. Companies that are aware of actual production capacities are already benefiting from this today. They have recognised the financial advantages of this important lever and are striving for continuous improvement – to the benefit of the entire value chain.

Increasing planning quality

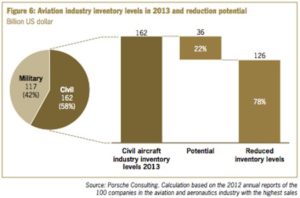

Improved planning quality refers to the agreement between planned and actual states, in order to display current performance levels and provide the necessary information to all partners. By increasing their planning quality, companies can reduce inventory levels on all steps of the value chain. This becomes possible when companies can rely on actual component availability and therefore reduce their buffers and reserves. The potential for reducing inventory levels on the basis of improved planning quality can be quantified. The results of this study show that it is possible to reduce inventory levels by an average of 22%. For a total inventory in the civil aviation industry of approximately US$162 billion, that means savings of approximately US$36 billion. Optimising inventory levels carries a large potential to liberate funds that can be reinvested to finance growth.

The basic prerequisites for utilising this potential are better in the aviation industry than nearly any other sector, because it shows a comparatively high degree of planning stability on the demand side. Its order books are full to bursting and its agenda for the next seven years is thus set. It is also the case that manufacturers’ forecasts on developments in air traffic have been consistently accurate historically, and even on the conservative side.

However, the survey shows that 29% of companies have thus far not paid any attention at all to planning quality. They are therefore missing the chance to improve this index by identifying and eliminating sources of error that lead to fuzziness in planning. The value therein can be seen by the other group, which does measure its planning quality. It achieves average planning quality of 80% and thus a significantly higher value.

Effective instrument: the “frozen zone”

One lever for raising planning quality consists of precisely specifying and then complying with production planning and manufacturing sequences. This is known as a “frozen zone,” in which the specified processes are strictly followed and can no longer be changed. Planning quality for those who have pioneered in introducing a frozen zone is around 90% – measurably higher than the 68% for those companies who have not started at all. “Reliability and improvement of medium and long-term forecasting quality with respect to suppliers lays a solid foundation for planning,” said one manager in noting the advantages of a frozen zone.

Companies that introduce stabilisation in the form of a frozen zone show an on-time delivery rate of 90% as opposed to 82% for those who do not. Incoming deliveries from suppliers show an on-time rate of over 95% thanks to this principle. The entire value chain benefits from this, because if major individual members of the chain do not fulfill their roles completely and on schedule, the overall system is quickly no longer in harmony. In their own interest, therefore, aircraft manufacturers need to create the corresponding framework conditions for bringing all suppliers up to the same standard.

Stable production operations also enable inventory levels to be reduced. Companies with lower planning quality levels reported disadvantages from having to maintain higher inventory levels in order to compensate for their customers’ fluctuating order levels. It is common practice to then exert pressure on partners to bridge shortages by means of additional short-term deliveries, especially with respect to logistics providers. But this does not produce the desired effect, because it does not correspond to the ideal of a stabilised production process and it requires additional time and resources. Reliable information on forecasting and ordering is the only way to ensure that the entire value chain functions smoothly.

Creating professionalism through a new understanding of roles

Demands on the market will change by 2020 and the members of the value chain have to adjust accordingly. Results of this study show that the roles and responsibilities of everyone involved in ‘The New Value Chain’ are being transformed. In the process, every member of the chain needs to work on a partnership basis to take on supplementary tasks, which should be coordinated as perfectly as possible. The companies will have to master the requisite core expertise needed in the future and must further develop as they work together to set aims for the overall system. One priority here is to have sufficient flexibility to respond promptly to short-term influences on the market.

Demands on the market will change by 2020 and the members of the value chain have to adjust accordingly. Results of this study show that the roles and responsibilities of everyone involved in ‘The New Value Chain’ are being transformed. In the process, every member of the chain needs to work on a partnership basis to take on supplementary tasks, which should be coordinated as perfectly as possible. The companies will have to master the requisite core expertise needed in the future and must further develop as they work together to set aims for the overall system. One priority here is to have sufficient flexibility to respond promptly to short-term influences on the market.

A key factor here is that the responsibility for controlling this network will start to shift. Instead of being performed exclusively by aircraft manufacturers, as has thus far been the case, this central task will be carried out to a substantial degree by the suppliers themselves. Their role in general will be greatly strengthened. In response to pressure from aircraft makers they will be producing a greater number of modules and more complex products independently while also assuming a more significant partnership role with respect to risk. The logistics providers will also have a considerably more prominent function than before.

Aircraft manufacturers

By the start of the next decade, the aircraft manufacturers will become the system architects and integrators within the value chain. Development continues to be their most important task, and has even gained 11% in significance. Responsibility for planning and coordination will thereby remain completely in the hands of the aircraft manufacturers, while implementation will be given over to the suppliers. As we see it, the aircraft manufacturers will be setting the tone, and are responsible for planning the overall structure of the value chain and its relevant suppliers. This shifts the emphasis for aircraft manufacturers from control to planning. Analysis of the study’s results shows that the latter has increased in significance by 12.5%.

The prerequisite for this development is the provision of stable forecasts along the supply chain, as well as a constant exchange of information. As of today, 58% of the aircraft manufacturers are unaware of restrictions in the production capacities of their suppliers, and a good 75% of them do not take this into consideration in their planning. By contrast, joint planning of the processes by all those involved under the direction of the aircraft maker will enable across-the-board communication of actual capacity needs. This is the only way to identify possible bottlenecks at an early stage and have sufficient response time to prevent or bridge them. This also makes it possible to reduce unproductive inventory levels for both aircraft manufacturers and suppliers.

This represents a substantial change in roles over the status quo. Aircraft manufacturers are currently alone in playing the central role in the overall value chain. Their most important task at present is to develop new airplanes and to specify and assign the various production tasks to suppliers. They also focus on manufacture and assembly, of the overall product as well as of individual segments and components. They thus fulfill a central function in controlling the entire supply network; this activity is an average of 16% more important for aircraft manufacturers than for suppliers. Nevertheless, aircraft manufacturers have thus far had little opportunity to control the supply chain via the first-tier suppliers, given that information in many areas is currently communicated to each of the suppliers individually. Transferring actual demand promptly into commercial orders placed with suppliers via a joint, uniform IT system has proven to be a central problem here.

Help from logistics service providers

Aircraft manufacturers will also be relieved of responsibility for most of their requisite inter-plant transport and logistics activities in the future. These will be taken over by logistics service providers – this is already suggested by the fact that manufacturers assign the lowest value to logistics up to 2020 in this study. In contrast to today this could mean, for example, that manufacturers’ own ship and aircraft fleets for component transport could be operated in the future by third-party companies.

Manufacturers currently bear the largest share of risk for development and production, at an average of 12% higher than for suppliers. Here, too, manufacturers desire to shift a greater part of the risk to partners within the value chain. Internal production issues will lose 5% in significance, while the purchasing volume for systems already integrated by suppliers will increase by half in the future, namely, from 40 to 60%. As such, the results of this study show that aircraft manufacturers will be assuming their new role as systems integrators while the supply base will be consolidating at all levels.

Suppliers

Suppliers, particularly those of the first tier, will become the link between aircraft manufacturers and the other suppliers. Following specifications from the aircraft manufacturers, they will develop complete systems solutions and guide the associated sub-suppliers on their own. As such, they will have to master a considerably higher degree of complexity in development, production, and logistics as they become systems suppliers and increasingly also a driving force behind innovation. Because not all current first-tier suppliers will actually be able to assume this role in practice, their total number will decrease. This is shown by the responses compiled in the study. The changing profile of requirements will also include establishing their own expertise in production scheduling as well as the ability to guide sub-suppliers.

Greater responsibility assumed by suppliers A 20% increase in significance for the changing role of suppliers was assigned to the supply of systems – the greatest such increase in this area shown by the study. The share of systems implementation on the part of suppliers will rise from the current level of 40% to 55% in 2020. Of note is the fact that this figure still lies below the expectations of aircraft manufacturers, who seek to purchase 60% of their volume in the form of integrated systems in the future. A large number of the suppliers will be systems manufacturers in the future. This means that first-tier suppliers will take on greater responsibility for controlling the supplier network, which will involve greater complexity and thus also greater demands on their role. For first-tier suppliers this also means expanding their own range of suppliers, because aircraft manufacturers will be handing over their contact to sub-suppliers. For a good half of suppliers, the number of sub-suppliers will increase, which is to be expected given the future decrease in the number of suppliers to aircraft manufacturers.

At the same time, ever more suppliers will be responding to pressure by the aircraft manufacturers and fully assuming risks on a partnership basis. The significance of this role has risen by 12%. The survey shows that suppliers are clearly assuming this role, which is also a basic prerequisite for becoming a systems supplier. First-tier suppliers will no longer be doing simple preassembly work anymore; instead, they will be passing on this work to second or third-tier suppliers or to logistics providers as their own field of work becomes more complex and thus of higher value.

Logistics service providers

Logistics service providers are more dependent than suppliers on planning by manufacturers. As the last link in the chain, they have to “suffer” the irregularities that have accumulated along the way. In the future they will advance to become an innovative interface within the value chain, although the greatest increases in significance continue to be anticipated in conventional logistics. Logistics service providers will be offering ideas on how to optimise the supply chain logistics and achieve the shortest possible response and delivery times worldwide. This also includes supplying and integrating markets in newly industrialised countries. Their value-added share in the “new” logistics disciplines will also increase.

Logistics service providers as highly flexible value-adding partners The value-added share of logistics services will also increase. Logistics companies will take on simple preassembly work such as cutting raw materials or checking the certification and quality of incoming goods. As their range of activity expands, they will grow from fulfilling an agency function to becoming highly flexible value-adding partners. They will thus be able to ease the load on the other partners and contribute their wage-cost benefits in a targeted manner to the overall system.

Integrated logistics systems will enable logistics providers to raise their profile as innovative partners in the industry. Logistics service providers propose and encourage ways of optimising the supply chain, even if they have less decisional leeway here than other members of the value chain. At the same time they have to be the most flexible component of the chain and be able to support a wide range of scenarios with short response times.

Conclusion

The high and secure level of demand and the resulting potential for growth offer a range of opportunities for all market participants up to 2020. However, closely coordinated interplay is needed to make optimum use of these opportunities. The problems observed in production and the supply chain require overarching approaches, which assume a central role in ‘The New Value Chain’. To smoothly handle the meta-orders of the future, the industry needs to focus consistently on operational excellence. This study shows the potential that exists to considerably increase on-time delivery within the value chain.

Range of opportunities for the industry

On average, companies see the potential for a 15% increase in on-time deliveries, and one-fifth of them consider a 30% increase possible. Improved coordination and more reliable planning would enable them to reduce inventory levels by an average of 22%, which corresponds to savings of US$36 billion. The companies surveyed estimated an average potential of 20% greater productivity from an optimised supply chain. This would yield estimated savings of US$1.4 million for the manufacture of each single-aisle aircraft with more than 100 seats. This is based on 70,000 hours of labour per aircraft at a cost of US$100 per hour, and a 20% increase in productivity.

To remain competitive, the aviation industry cannot allow so significant a degree of potential to remain unused. With ‘The New Value Chain’, aircraft manufacturers and their suppliers can be a guide that pinpoints the paths they should take in order to be fit for the future and to benefit in a sustainable manner from positive developments on the market.

Study basis

Aircraft manufacturers’ full long-term order books and relatively stable delivery rates on the one hand, and high delivery fluctuations within the value chain with major delivery delays and order backlogs on the other provided the justification for this study.

Experience from more than 200 projects that Porsche Consulting has supervised since 2005 in the aviation and aeronautics industry has convinced us that the industry has to undergo change in order to meet its own aims in terms of delivery rates, on-time delivery, and profitability. To achieve the necessary change, the industry’s mechanisms cannot be taken individually but rather only as a whole.

In order to identify the tasks that the members of the value chain will have to assume in the future and how the inter-play within ‘The New Value Chain’ should function, Porsche Consulting surveyed 80 managers in Europe, the USA, Russia and Asia at the world’s largest aircraft manufacturing companies as well as at their supply and logistics partners. These individual interviews were held in July and August 2013 on the basis of structured questionnaires to ensure a high degree of comparability for the responses given.

About Porsche Consulting

Since its inception in 1994, Porsche Consulting has been conveying the principle of “lean and successful” to companies in a wide range of sectors. This principle originates from the parent company of Porsche AG. It derives from the vitally important restructuring process that the sports car maker had to go through in the early 1990s. The methods that emerged from this process are regarded as exemplary worldwide, and are further refined on a continuous basis. That is entirely in keeping with Porsche’s approach of never being satisfied with current achievements but rather trying to improve them a little more every day. We consultants call the path that leads to this end “operational excellence.” By that we mean the willingness and ability of an organisation and its employees to consistently deliver superior performance. Not just in certain areas but in all relevant business processes across the board.

Aviation and aeronautics have developed into one of our focal areas. Since 2005 we have successfully concluded more than 200 projects in the many different areas of this diverse industry. From the deep insights we have gained in the process, we recognise the scenario the aviation industry is now facing: the enormous anticipated increase in air traffic and the associated growth will bring most of the participants in the market to the limits of their capacities. In the view of Porsche Consulting, those who wish to spread their wings here will need a systematic approach in order to continuously increase their performance. A consistent new way of thinking is the only way to effectively address the constant delays in delivery, difficulties in raising production rates, and less than satisfying developments in profit. Tom Enders, the CEO of Airbus Group, has assigned a numerical value to these challenges in noting the need for an EBIT of at least ten percent to finance future technologies and further expand global growth in aircraft construction.

We have taken this situation and studied it with an eye toward practical applications. We wanted to know first-hand the extent to which production can be increased in the aviation industry at large if effective leverage is applied. Our study included individual interviews with 80 managers at aircraft manufacturing companies and their suppliers and logistics partners. The results show that sufficient potential is there. Actually making use of this potential, however, will require a radically new process and a future-oriented new approach on the part of all partners in the industry. This step is unlikely to be easy for anyone. However, with this study developed from our ‘The New Value Chain’ consulting programme, we clear the way for overarching solutions that can allow profitable growth for the industry in the future.

Written by Joachim Kirsch, Partner Aerospace, Porsche Consulting GmbH