At 6.30pm on 2 June 1910, aviation pioneer Charles Stewart Rolls took off alone in his flimsy biplane from Swingate aerodrome, near Dover, to achieve the world’s first non-stop double crossing of the English Channel by aeroplane.

Rolls (best known as a co-founder of Rolls-Royce) had been waiting in frustration for over a week, his departure repeatedly frustrated by high winds, fog or mechanical problems with the machine. But finally, conditions were perfectly calm and clear. Among the spectators on the cliffs were Rolls’ parents, Lord and Lady Llangattock, and his sister and brother-in-law, Sir John and Lady Shelley.

According to a report in the Daily Telegraph newspaper, Rolls reached an altitude of 900ft and a speed of “quite forty miles an hour” as he approached the coast of France. By 7.15pm, he was flying over the small French town of Sangatte, where the present-day Channel Tunnel emerges. Leaning out of his aeroplane, he threw overboard three weighted envelopes, each containing the message: ‘Greetings to the Auto Club of France… Dropped from a Wright aeroplane crossing from England to France. C. S. Rolls, June 1910. P.S. Vive l’Entente’’

He then turned northward and set a course for the English coast. At 8.00pm he was back in Dover where, the Daily Telegraph reported, “the sea front, cliffs and piers were thronged with people, all in the most intense state of excitement.”

Rolls rewarded them in typically flamboyant style, by flying in circles around the outer towers of the town’s medieval castle. “I decided that, as I had plenty of petrol and my engines were working splendidly, I would encircle the Castle, although it would lengthen my flight considerably,” he told the Telegraph correspondent.

The crowd loved it. This was more than mere entertainment: they knew they were present at a moment in history.

In an adventure lasting 95 minutes, Rolls had achieved two immortal landmarks. He had become both the first Englishman to fly an aeroplane across the English Channel, and the first aviator ever to fly non-stop from England to France and back again.

The flight caused a sensation and made Rolls an instant national celebrity. The recently crowned King George V sent a personal telegram, which read, ‘The Queen and I heartily congratulate you on your splendid cross-Channel flight. George R.I.’

The Aero Clubs of both England and France presented him with special awards. London’s Madame Tussauds even began making a waxwork of him. Flight Magazine, meanwhile, lauded his Corinthian spirit, loftily assuring its readers that Rolls had made the crossing not in the name of “merely winning souvenirs” and “without the smallest monetary inducement” – a claim that may have rankled somewhat with Rolls, who had spent almost £333,000 (at today’s prices) of his own money on flying in the first half of 1910 alone. It was perhaps with this in mind that he wryly remarked: “It is the only time I have succeeded in taking ten gallons of fuel in and out of France without paying duty.”

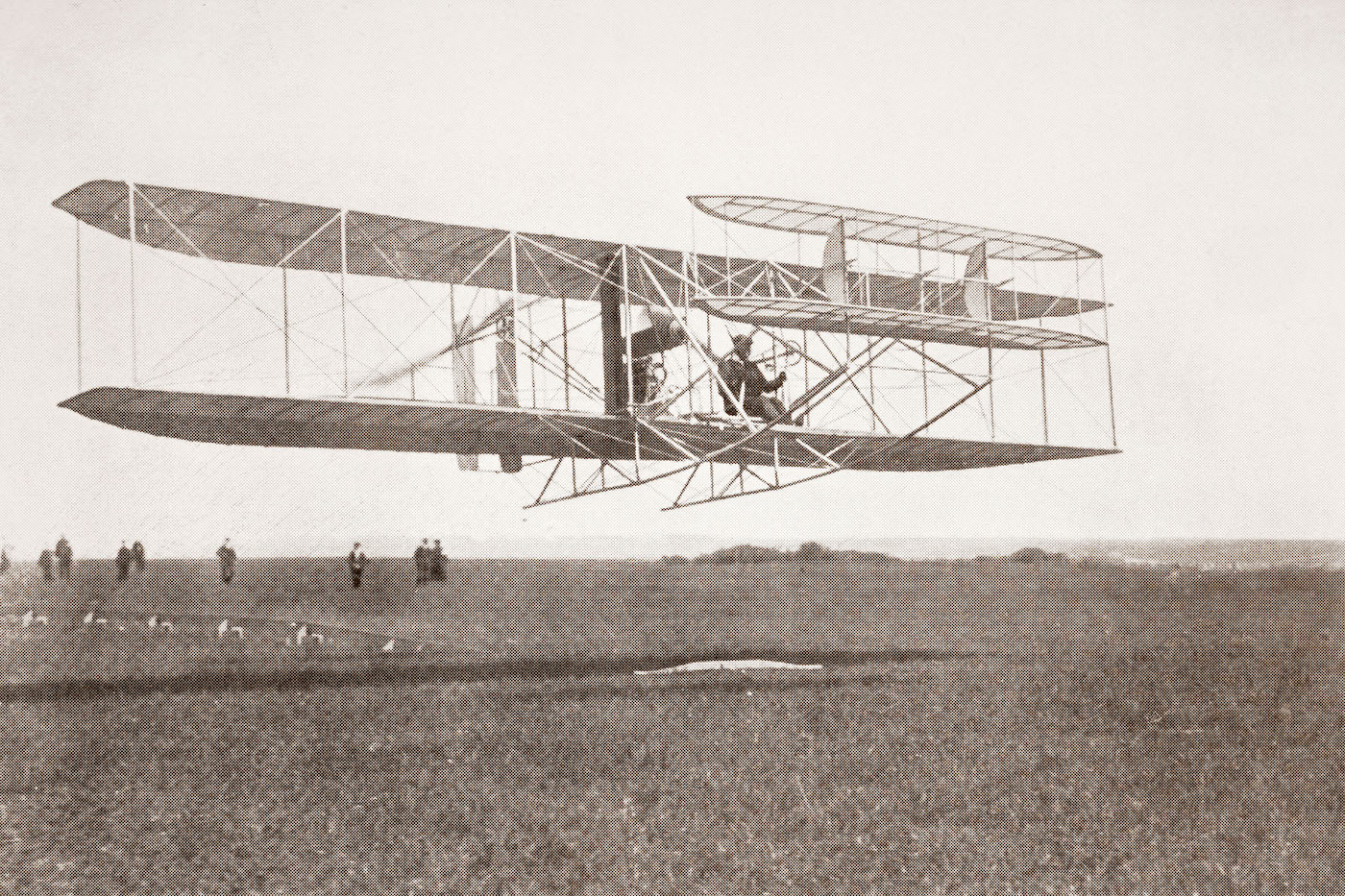

It is a sign of how quickly aviation and aeroplanes were developing that Rolls’ record-breaking flight came less than a year after Louis Blériot had stunned the world with the first powered flight from France to England in July 1909. Rolls made his double crossing in a Wright Flyer, designed by Wilbur and Orville Wright, who had recorded the world’s very first flight in a heavier-than-air machine just seven years earlier in 1903.

This timescale underlines the truly perilous nature of Rolls’ adventure. His aeroplane, built from wood and fabric braced with spars and wires, had a wingspan of just 12m (40 feet) and weighed only 457kg (1,008 lbs) including the engine – about the same weight as a grand piano. The physical dangers of crossing the sea in so primitive a machine are obvious; it seems Rolls himself decided to attempt the return trip only when he was actually over Sangatte and had reassured himself everything was working well.

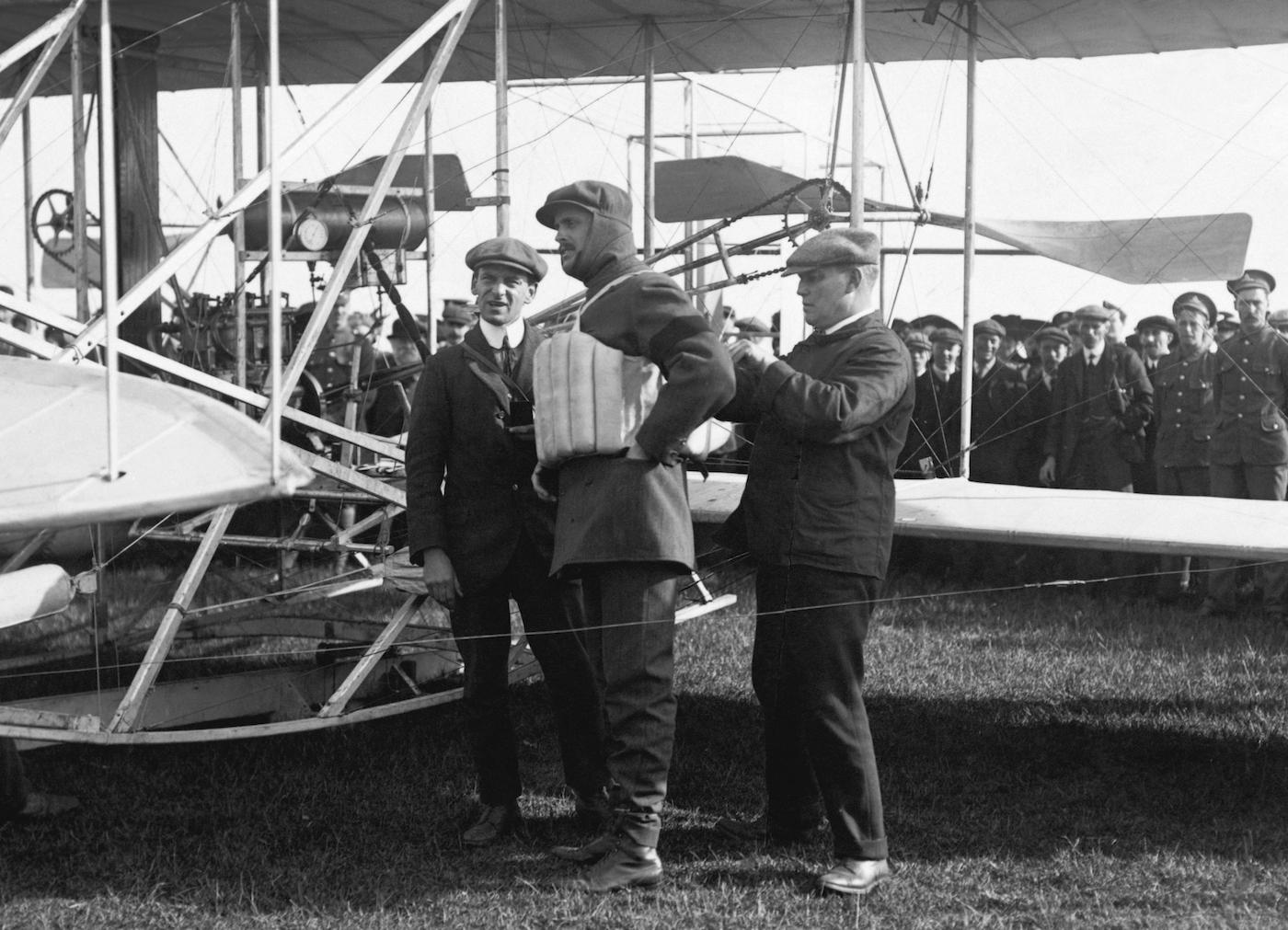

His sole concessions to safety were a lifejacket for himself, and four large buoyancy bags filled with compressed air lashed to the machine’s undercarriage. The Daily Telegraph noted laconically, ‘Happily, there was no need to test their efficacy’.

But Rolls was as experienced as he was daring. His flying career spanned what was then virtually the entire history of aviation. Born in 1877, Rolls had been fascinated by engines since his schooldays – he went on to earn a degree in Mechanical & Applied Science from Trinity College, Cambridge – and was captivated by flying from its inception. He was a founding member of the Royal Aero Club, initially as a balloonist, making over 170 flights and winning the Gordon Bennett Gold Medal in 1903 for the longest sustained time aloft. In the spring of 1909, when the Wright brothers came to England from America as guests of the Royal Aero Club, Rolls acted as their official host. A year later, he became only the second person in Britain to be awarded an aeroplane pilot’s licence.

After their historic first meeting in 1904, Rolls tried to persuade Henry Royce to build an aeroplane. He failed – one can only speculate as to what marvels might have resulted had he succeeded – but undeterred, Rolls bought a Wright Flyer in which he made more than 200 flights.

Tragically, it was in such a machine that Rolls met his death just a month after his cross-Channel feat. On 12 July 1910, during a competition at Bournemouth, the tail-piece broke off and the aircraft plunged to the ground from a height of 100ft, crashing close to the crowded grandstand in a tangle of spars and canvas. Rolls sustained a fractured skull and was pronounced dead at the scene; he was only the twelfth person in history to be killed in a flying accident, and the first Briton to lose his life in a powered aircraft. He was just a few weeks short of his 33rd birthday.

Although Rolls is vastly more famous today for his automotive achievements, his contribution to aviation was immense and important. In April 1912, a statue commemorating his double Channel crossing was erected in Guilford Gardens on Dover’s seafront; it now stands in Marine Parade Gardens, where it was rededicated on 2 June 1995 by the then-chairman of the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust.

Torsten Müller-Ötvös, CEO of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, said, “Charles Rolls combined a fine technical mind with a bold, adventurous spirit; it is no wonder that aviation and motoring held such powerful, almost magical attractions for him. He was a true pioneer in both fields, instrumental in the development of aeroplanes and motor cars with his record-breaking feats.”

He added, “Rolls challenged the limits of what was believed possible and, as his cross-Channel flight demonstrated, dared to venture beyond them. In so doing, he took technology and human ambition into wholly new territory. That he achieved so much in so short a life is extraordinary and inspiring. His imagination and courage are still very much alive in our company more than a century later.”

Müller-Ötvös concluded, “It seems particularly appropriate to remember his remarkable flight this year. Apart from the historical significance of the 110th anniversary, it comes at a time when we still face severe restrictions on our freedom to travel and explore. It encourages us to keep looking outwards, over the horizon, and dreaming of adventures we’ll take in the future – a reminder that anything is possible.”