Airlines are looking for green strategies to reduce the impact of their operations on the environment and are devising new ways to reduce waste, especially plastics. Ryanair was the first airline to make a commitment to fly 100% plastic-free by 2023, eliminating all non-recyclable plastics from its cabin service. A number of airlines have made similar announcements, such as American Airlines, which is cutting plastic straws and stirrers from its inflight service, in favour of biodegradable alternatives.

But the cabin interiors themselves could pose a danger to the environment. They may contain a large quantity of plastics, composites and hazardous materials, which should be handled with care at the end of their service life.

For a solution, we spoke to Tony Seville, owner of AIRA (Aircraft Interior Recycling Association), which has set up a recycling facility in the UK that breaks apart interiors components into reusable and recyclable parts. “We separate all of the metal frames from the plastics, seat cushions and seat covers, and wiring if IFE is installed,” Seville says. “The seat covers are baled for recycling and can be reused for yarn, which can be used in new carpet tiles or carpet underlay. Seat cushions are also baled for recycling.”

One of the challenges in the process is that aviation plastics are difficult to categorize. “There is no code to identify what type of plastic it is,” Seville explains. “The majority of them, we have learned to identify in various ways, but there are several types of plastic within the cabin, which, if not properly identified, can cause cross-contamination, so identification and segregation is key.”

Seville and his team are able to recycle many plastics that have second-life applications in other industries and have partnered with some industry suppliers to collect plastics from their customers.

“We’re working with Boltaron and its UK distributor Amari Plastics to pick up all of their UK manufacturing customers’ plastic waste, and we recycle this into reusable plastic. The only thing we’re not allowed to do is put it back into the aerospace industry,” Seville explains.

Seville has developed a sorting and preparation process and also reached out to Warwick University in the UK for guidance.

“A lot of plastic seat parts from old seats mostly contain double-sided tape – this needs to be removed, otherwise it contaminates the plastic recycling process. It can be done, but it is time-consuming. Some parts have metal, glue or silicon on them and have to be removed if possible, and if not they go straight into the waste bin, to be sent to landfill,” Seville says. “Luckily this only adds up to about 1% of the entire recycling process.”

Any plastic parts that have been repaired and painted with various fillers to mend cracks must go directly to landfill because those patches can contaminate the good plastic and ruin the recycled end product. Any contaminated product must go to landfill.

“Any plastic product within the aircraft cabin can be recycled if it is clean and free of contamination,” Seville says.

Numbers needed

“What the interior manufacturers in aviation need to start doing is putting an [identifying] number on the plastic. Most plastics have a code from one to seven, so that you know roughly what type of plastic it is. This labelling may have already started on newer interiors, but on the older interiors that we are recycling, it’s not apparent.”

Seville says that, working with Warwick University, AIRA is testing plastic materials to identify them for second-life, by determining their properties.

“They are really taken aback with what we are doing; and also that there is no regulatory body that has control over what materials are being used, and that no one has taken responsibility for recycling of the materials that make up the interiors, like the automotive industry has,” he says. “The auto industry has worked on a system where the materials they use in the car can be identified and will be recycled at the end of service life. This is where our industry needs to be,” he adds.

Cost incentives

There is a lot to be salvaged from a cabin, and a big cost-incentive to avoid landfilling seats. The typical weight of materials for a shipset of seats from a 180-seat narrow-body aircraft such as an B737 or A320, without IFE and without composite back frames, contains 3,086 lb (1,400kg) of metal, 880 lb (400kg) of seat foam, around 440 lb (200kg) of seat covers and 660 lb (300kg) of plastics – that’s a total of 5,070 lb (2,300kg), or 2.3 metric tons.

“It can cost about €4,500 [US$5,000] to send a shipset of seats with IFE and composite back frames with a combined weight of 2,300kg to landfill. The lowest cost would be €2,000 to €2,500 [US$2,300 to US$2,900] for seats without IFE and composite back frames, depending on the landfill site,” Seville says. “Not all landfill sites will take hazardous waste or composite materials and will charge a fortune to handle them and dispose of them.”

Seville says that some airlines and other suppliers store shipsets indefinitely, considering them assets. But the value of these assets depreciates. Without a plan for repurposing or recycling they become cost burdens, not just in warehousing, but ultimately in disposal to landfill.

“Let’s say, for argument’s sake, a company has six shipsets of seats [1,080 pax places] that are already seven years old, stored in a 10,000ft2 warehouse for the last five years, and the cost per square foot is €9 [US$10]. Over the five-year period, the seats have cost €448,000 [US$520,000] to hold as a depreciating asset. They were probably worth around €670,000 [US$780,000] when first put into storage. When five years pass, the company wants to move the seats on, but there are no takers because the seats are now 12 years old. What does the company do with them? There are no options, only landfill,” Seville says. “Everything has the potential to have a value.”

Beyond recycling, interior parts that are in good condition can be segregated for reuse and re-introduced back into the supply chain. Parts can be cleaned and inspected and recertified with full traceability, in order to be sold on to a new clients.

“The one thing you can’t get from interiors easily are spare parts. We know that airlines need interior spares on a regular basis. We are trying to build an interior spare parts distribution centre in the UK where the parts would be able to be sold onto new clients instead of going to the landfill,” Seville says.

AIRA also has a scheme to share 30% revenue from the parts that it sells on to the airline or whatever company owns the interiors.

“There’s an incentive there for them to send owned seats and interiors to us – to either recycle or reuse – that would otherwise end up in landfill,” Seville says. “We’re looking for airlines to recognize that they don’t have to hold it and keep parts forever.”

Landfill costs, but recycling or reuse is cheaper, and it’s recycled correctly.

Seville believes the industry must think of asset value beyond the initial purchase price, to the full service life and second life of the products. This may mean planning ahead, marking the class of plastics on the component, just as the industry marks all parts for full traceability by regulatory standards. Manufacturers and designers can also think ahead to recycling and repurposing by considering where they use laminates or decorative elements that require glue.

“Everything we have has a value. It’s how we deal with it, whether we make it economical to recover that value, that is the key for recycling,” Seville says. “There is now an opportunity for seat and interior manufacturers to go to the likes of Boeing and Airbus and airlines and say, ‘Buy our seats or interiors because they can be recycled at the end of their service life’.”

Go green early

During the Passenger Experience Conference at Aircraft Interiors Expo this year, industrial designer and circular economy expert Christina Fagin of Grüner Hering, suggested that aviation industry designers and engineers need to be involved in product development earlier on, looking for a business model that supports a green lifecycle and includes plans for second-life applications of components. She suggested that the focus for today’s manufacturers should be to retain the value of products both in resources and built parts.

She identified four potential lifecycles or ‘loops’ that help retain value. Some of these are already in place for aircraft interiors, including refurbishment. “The first loop is to try to keep them in use for longer. That can be done by building high-quality products, selling them once, and adding services like care or consumables – like selling the detergent instead of the washing machine,” she said. “The second loop is sharing, ensuring that the product can be used more efficiently throughout the same lifetime. The third loop is product reuse and the parts reuse. Then, you must collect the products, refurbish them, and put them on the market again and create more revenue through that. I know of a company in the Netherlands that does this with office furniture. They sell it and have a contract with the client that they will buy it back after a seven-year period, refurbish the furniture and sell it again. They do that three times and, in the end, they create 25% more revenue and can offer their products to a broader client range because not everyone can afford the higher-quality first product. The fourth and last loop is material recycling.”

Recycling, she emphasized, requires that manufacturers can identify the specific material components so that they can be properly processed. Repurposing products also requires planning ahead, designing for second life to preserve the maximum value. That may involve designing products that are easier to repair and repurpose, or easier to disassemble to recover second-life parts. It will include marking parts for easier recycling. There are a variety of strategies that make repurposing or recycling easier, but the key to retaining product value is to avoid re-introducing a heavy cost burden to the second-life process.

“The more supply chain stages, the more that you have to go through again to make the product go back to market,” she said. “That also means more input. If you have material recycling, you still have to put more energy and labour in before you can sell the product again. The higher value is in the inner loops, where the most attractive business models are. The smaller the loop, the more profitable and resource-efficient it is. Don’t repair what is not broken, don’t remanufacture what can be repaired, and don’t recycle what can be remanufactured.”

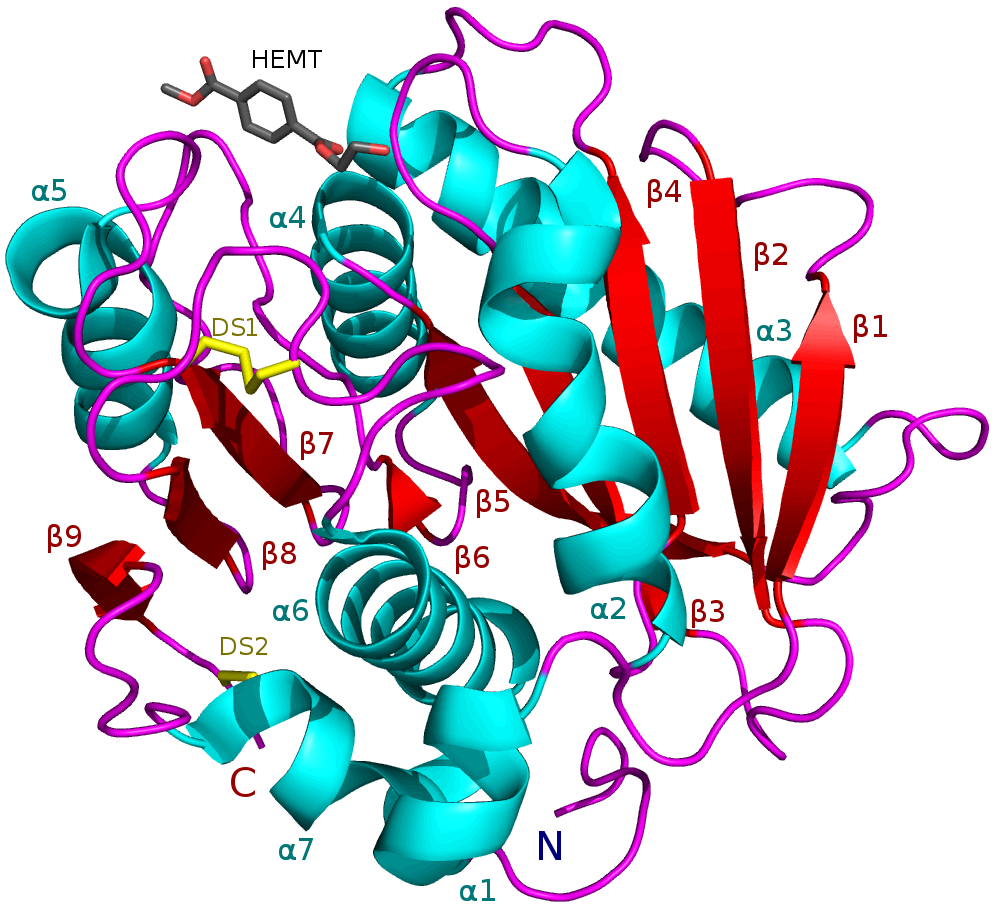

Image: Keministi

IFE issues

IFE components in interiors also require careful sorting and pose unique environmental challenges.

“Wiring and plugs are recycled, along with circuit boards, which contain precious metals,” Saville says. “LCD screens must be handled with extreme care as they contain CCFLs (cold cathode fluorescent lamps). CCFLs contain a small amount of mercury, which is toxic and is classed as hazardous waste. If not recycled correctly, these screens can cause serious problems, if they fall into the wrong hands. Some 5-10 of screen types contain enough mercury to pollute 30,000 litres of water, beyond the safe drinking level in the UK. So, if you are thinking of sending your old seats to landfill, then think again. You must let authorities know what materials you want to recycle, so that they can charge you accordingly, for handling hazardous waste and for the landfill tax.”

Eco Compass

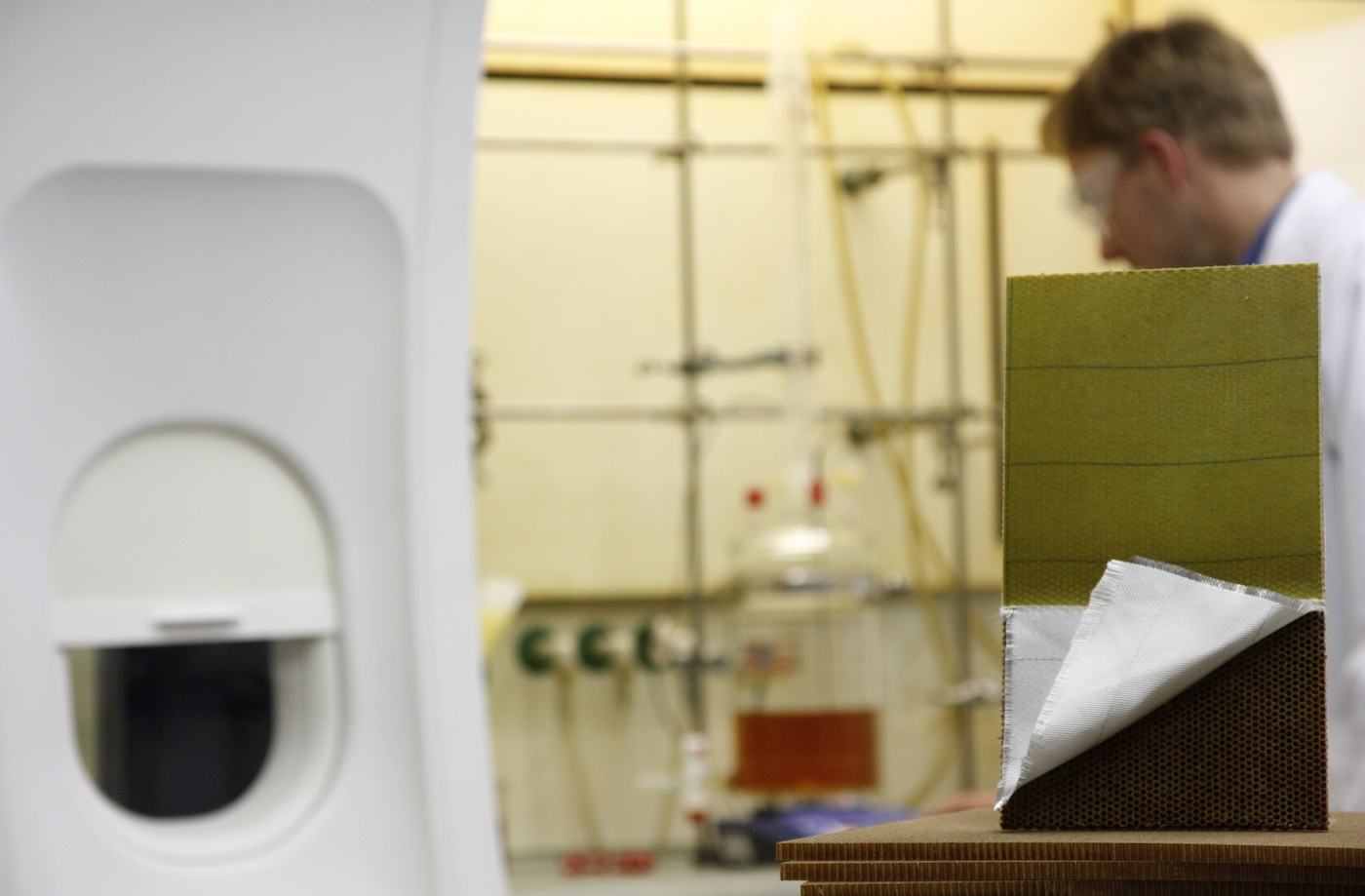

A Euro-Chinese project is underway, aiming to develop and assess multifunctional and ecologically improved composites from bio-sourced and recycled materials for application in aircraft secondary structures and interiors. Named Eco-Compass, the 36-month, €1.9bn project has 11 Chinese participants and eight European, including Airbus Group Innovations, AVIC and various research organisations and universities.

The partners acknowledge that the lightweight structures used in modern aircraft have excellent mechanical properties combined with low weight: for example the GFRP used in aircraft interiors and the CFRP used for fuselages and wings, etc. However, they also feel that all these composite materials are man-made and energy-intensive to produce, and that renewable materials such as biofibres and bio-resins could be a greener alternative for composites.

The 50 researchers and engineers on the project are now assessing the use of ecologically improved composite materials for interior and secondary structures, including bio-sourced and recycled fibres, bio-sourced resins and sandwich cores.