Looking back at the past 20 years of cabin design, there have been some impressive advancements, including seeds planted for improvements that will re-shape air travel for the next two decades. As PJ Wilcynski, associate technical fellow and payloads chief architect for Boeing, states, the basic principles of cabin design endure, adapting to and benefitting from new technologies and capabilities.

“We believe there are some unchanging drivers for cabin design, and a few of these things that have guided us for the last 60 years,” Wilcynski says.

Boeing has distilled these drivers into three basic needs: a place for things, a view to the outside, and feeling connected to the sky. Improvements made to the aircraft cabin, including technology upgrades, are created with these principles in mind.

Boeing has worked to deliver on those design principles over many years, including innovations like the automated tinted windows of the B787, a concept of comfort that can be traced to an original mock-up for the B707 cabin in the late 1950s, which included tinted visors.

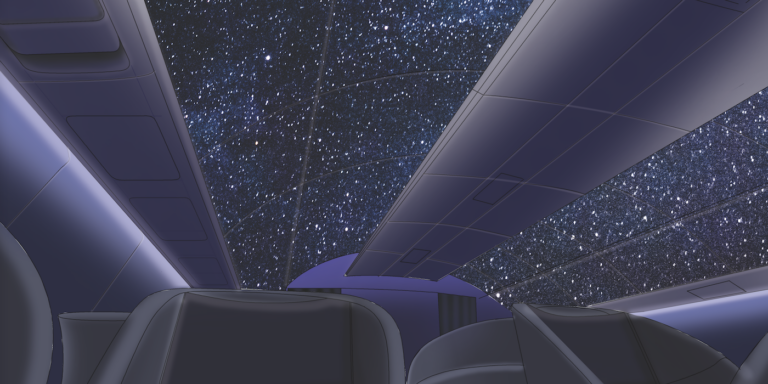

Likewise, the notion of the Starry Skies lighting effects on the B777 cabin was first conceived for a B707 mock-up, which included Sky Domes. Looking forward to the next 20 years, many of the experiential improvements Boeing expects to see in the aircraft will help passengers break free of the confines of the cabin, giving them a unique connection to the sky, as close as possible to realizing the original dream of flight.

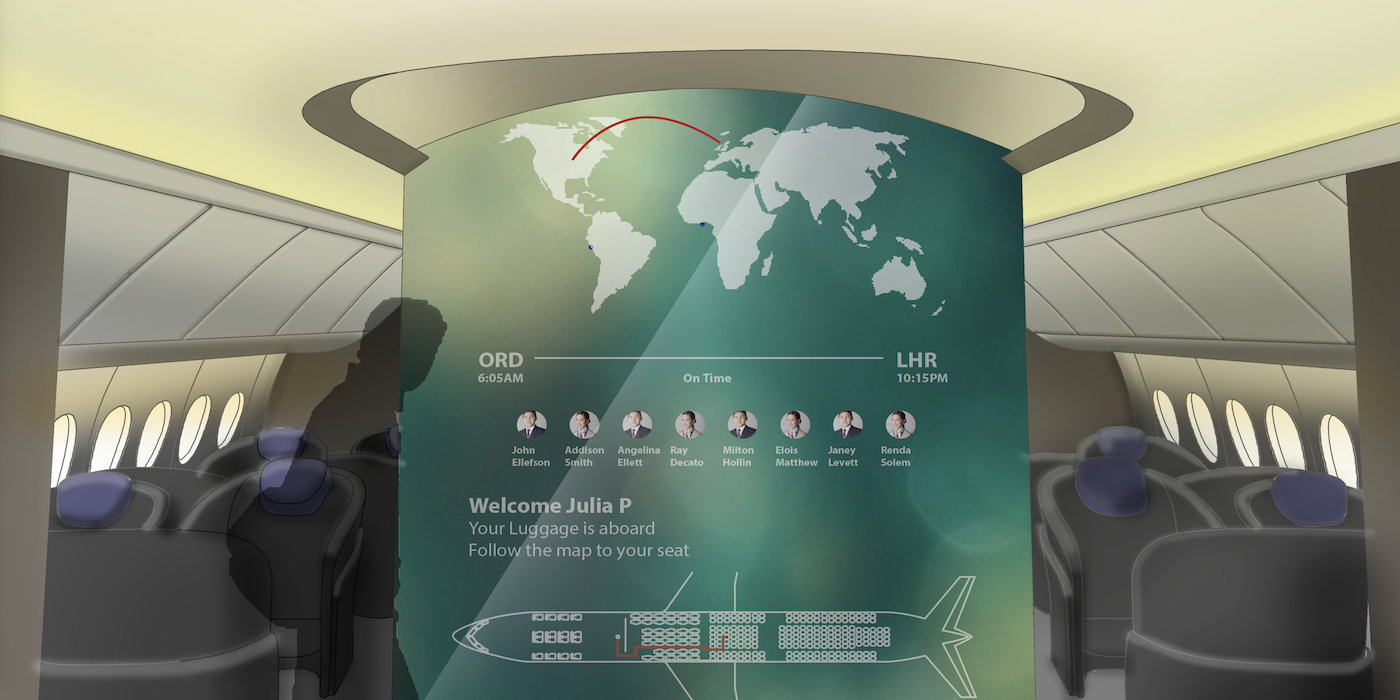

“When we look at the journey map, it hasn’t changed over the years. There’s boarding, personal time, meal time, rest, refreshment, landing and deplaning. What has changed, and what will change in the next 20 years going forward, is what we call ‘ubiquitous continuous connectivity’. That’s airplane to crew, crew to airplane, passenger to airplane, airplane to passenger, and airplane to the world,” Wilcynski says.

As technology evolves, Wilcynski expects that it will help make the aircraft more ‘aware’ and responsive to the needs of passengers and crew, while also helping make passengers and crew more aware of each other and of their environment.

Major milestones

Looking back 20 years to major milestones along the path of the passenger experience improvements we already enjoy, Wilcynski highlights the introduction of the B777 family of aircraft.

“That was the first aircraft interior to win an industrial design award. That was the start of really significant recognition by Boeing that passenger cabins can be beyond the purely functional, that you can take it to the next level from an aesthetic standpoint,” he says.

Of course, the B787 Dreamliner has also been a major milestone, its design extending to other Boeing aircraft.

“Shortly after 2000, at the change of the century, we started on a journey to develop the B787 interior. What we now call the Boeing Sky interior was then propagated into the B737, the B747-8 Intercontinental, and now we’re looking onward from there,” Wilcynski says.

“From a cabin perspective, in those 20 years we’ve really recognized the value of great design and of embedding appropriate technology to enhance the cabin experience.”

Dealing with crises

Wilcynski also notes that the industry has been evolving during this period, with changing airline brand strategies.

“In 20 years we’ve seen this extreme differentiation by airlines, an exploration that has provided a full range of opportunities to explore our cabin designs,” he says. He believes that the industry has progressively advanced in its passenger offerings, even though the past 20 years have included the tragedy of 9/11 and the financial crisis, both of which negatively impacted airlines.

“The low times, from an economic standpoint, drove them to consider how to get a get a larger share of those premium passengers. I think airlines accelerated a bit in their understanding that, to attract the premium passenger, they really had to differentiate. Some of our customers were differentiating in economy class, but differentiating to gain premium passengers was crucial,” Wilcynski says. “They did that primarily in those things that we really don’t control: seats and other furnishings in the cabin, quality of materials, onboard services, and other services removed from the aircraft, like picking you up at your front door or driving you up to the airplane.”

In that push to attract high-revenue flyers, Wilcynski credits airlines for helping spur innovation by raising the stakes. “All of our customers are very demanding, and rightly so. That can be in many different ways, but airlines always find a way. They see opportunities and they push us, which is a good thing.”

Wilcynski states that introduction of the Dreamliner has helped airlines achieve differentiation, improving global networks, and better connecting the world by opening up new routes for city pairs that weren’t previously viable. The Dreamliner program also presented fresh opportunities to engage passengers in research and development. In many ways, the Dreamliner was the world’s first crowdsourced aircraft.

“It has also been very interesting and heartwarming that we get as much feedback as we do,” he says. “The testing that we did with thousands of people on the ground as we developed the Dreamliner led to our design and served for subsequent airplanes. The Dreamliner name itself came from both customer research and online feedback, in the early days of AOL. We had literally tens of thousands of people around the world looking over our shoulders and participating both on the ground and online to help us design that airplane. What’s really gratifying is that people around the world are now flying in it. They never dreamed of that before.”

Dare to dream

Delivering on the promise of the Dreamliner presented a number of new challenges to the cabin designers.

“Like the rest of the B787, the interior has a lot of advanced technology. This took time to develop. Specifically, I could point to the windows, and other technologies from the lighting perspective, which required enhancement and refinements as time went on. We had advanced materials for the electronically dimmable windows, and the control systems for those were very novel, especially to be introduced as broadly as they were on the B787,” Wilcynski says. “The combination of new technologies and new materials on the B787 was probably the biggest challenge.”

But Wilcynski sees those challenges as being personally very rewarding. “When we developed the lighting, that was the fun part. We knew what we wanted to do. We had the technology, with a few bumps, of course. Creating the lighting scenes was some of the most fun I’ve had on the B787 program.”

The next 20 years?

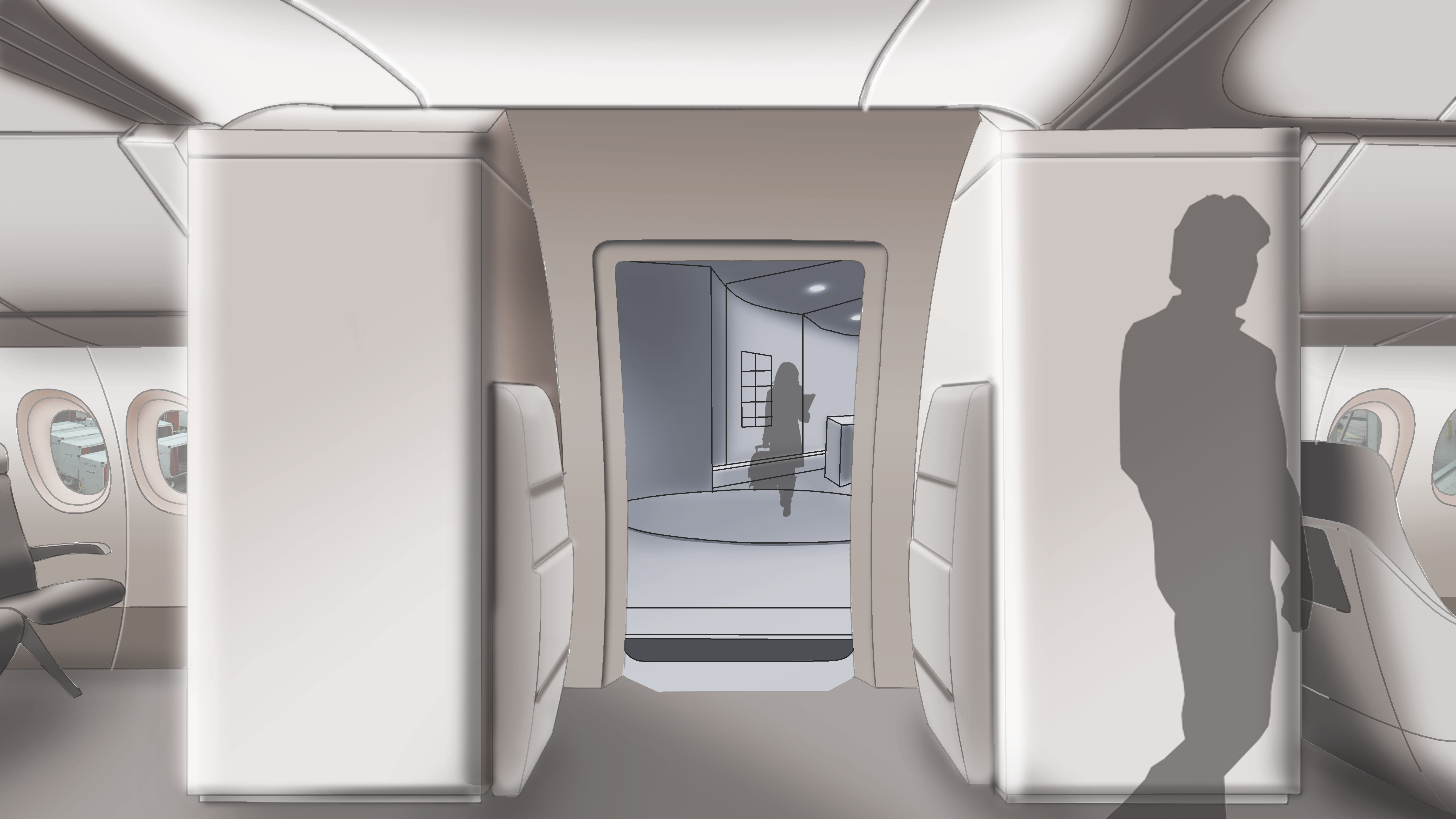

Looking forward to the next 20 years, Wilcynski expects that connectivity will play a continued role in cabin design, not only the connectivity we commonly think of today, facilitated by data networks, but the connection between passengers and the aircraft, and the experience of flight, addressing the three basic needs around which Boeing design is focused.

“I don’t think there’s anything unique that changes those key drivers of design,” he says. “They don’t change. They get enhanced with more information, or waiting for appropriate and proven technology to enhance them. With Starry Skies, which we now do with fiber-optics, perhaps it will be done with some sort of projection system, or at some point with an OLED system.”

Wilcynski can imagine aircraft that create more interactive experiences for passengers, with images from below projected onto class-divider panels. For example, a program that might project sightings of whales in the water, so that passengers can enjoy them.

Enhanced lighting programs could create unique experiences, such as a projection of floating lanterns on the ceiling, to accompany meal times, and nightscapes of the stars, including the position of the constellations relative to the phase of flight. These experiential features might also be projected to seatback displays, but Wilcynski believes that the focus of design should be to make flight a less isolating experience.

While there are many benefits to individual comfort and entertainment choices, passengers should also feel that they are enjoying an enhanced flying experience together, he believes. That said, some individual experiences can be improved through a greater awareness of the ground and enjoyment of flight, at least for those with window seats. Informational projections on windows could point out sights and special features.

Other technologies that may shape the future of the cabin include additive manufacturing, more commonly known as 3D printing, but while Wilcynski sees great potential in this technique, he believes there will be technical challenges to overcome. “There’s going to have to be a lot of development to get to that point where you say, ‘Okay, we can now do 3D printing for the structural elements that meet both flammability and structural substantiation’,” he says.

Will windows remain? And what of modular cabins?

Wilcynski believes that ensuring that connection to the flight experience, by preserving windows, will still be important in future cabin designs.

“I would struggle with modules, personally, and from a design point, due to the importance of windows. Of course, there’s nothing to say that you couldn’t have windows on modules that would connect with the windows of the aircraft. Many don’t know that the Boeing has had this capability for close to 40 years. We’ve built what we call Combi, or converter aeroplanes, which have the freighter door and allow for overnight conversions.

“In those cases, everything is built into a platform. The windows are constructed and they would allow conversions between various seating configurations on a palette, or all-cargo configurations, or whatever an airline wanted. It’s all done simply by the palette, not necessarily by a complete module.”

Wilcynski struggles with the notion of modular cabins, although he believes airlines will want cabins to be more adaptable, enabling airlines to quickly adapt to new opportunities in the market.

“Let’s say a new kind of premium economy is introduced, or an enhanced economy that is one step below premium economy but is not basic economy. If it’s determined that there are certain cabin features that have to be provided, that could be accommodated,” he says.

“But at the top of every airline’s list is efficiency. When we talk about cabin modules that would require a freighter door built into the fuselage, and some sort of transferring system built into the floor, both of those add weight to the aircraft. So, for that flexibility, they would pay a significant weight penalty of several thousand pounds, for every flight. That’s why, when I think about modularity, it has to be the sort of modularity that can be broken down and then passed through a passenger door, which could then easily adapt to what an airline wants to do with the passenger cabin.”

There is also a possibility of kitting certain cabin elements, so that they are easier to install and change out.

“I remember many years ago that there was a galley that wheeled onto the airplane and latched onto the floor,” he says. “I think there’s possibility there, but it’s really going to be the airlines that lead it. Every time that you do kitting of that nature, you are incurring penalties for weight, and there are always the certification aspects of how that is handled.”

Wilcynski also cautions that, with regulatory requirements, a “quick change” of modules may not be as quick as we think.

“Any change to the configuration of the aeroplane requires a service bulletin,” he warns. “Perhaps it’s an easy conversion, but it still has to be completely installed, certified, and found compliant in conformity, under the auspices of a Service Bulletin, which then has to be executed and inspected.”

How about Blended Wing Body (BWB) designs?

Asked about blended wing aircraft, Wilcynski modestly answers that the viability of the aircraft itself is beyond his purview, although he has some notion of what might be required for the cabin design of such an aircraft.

“I know we’ve talked about it for many years, and I hesitate,” he says. “If I look at what I think is important in the passenger cabin, I think it would be a very different perception. It would have to be an extreme focus on architecture.”

However, he tells us, that the introduction of virtual reality, or augmented reality, could open-up possibilities.

What are your favorite cabins over two decades?

Over the decades that Wilcynski has worked at Boeing, dealing with seating and cabin design, he has seen many trends come and go, and new technologies emerge to become new service standards. We ask Wilcynski whether he has a cabin of which he’s particularly fond.

“I do have a personal favorite, from pure aesthetics,” he confides. “When we took the B777 interior and redesigned it to go into the B767 family, it was spectacular. It just had fluorescent lights – it didn’t have anything fancy – but it was a spectacular interior in its form alone.”

So form that fits function, even simply, can be enduringly elegant. But the function and experience of flight is far more than transporting people from point A to point B, and Wilcynski hopes the industry will never lose sight of that.

“I would hope that we can still preserve a joint travel experience in the cabin, so that we don’t lose the feeling that we are on a journey together. I worry that everybody is too focused on their electronic devices and that we lose that excitement of ‘Hey, I’m up in an airplane at 40,000ft’,” Wilcynski says. “The wonder of flight, the magic of flight, is just incredible. I hope someone opens the windows once in a while.”

And what of inflight connectivity?

Inflight connectivity with access to the ground will facilitate a number of experiential and operational features, Wilcynski predicts.

“The developments that I see are large touchscreen surfaces in the cabin. The challenges are going to be structural substantiation and flammability of those large surfaces,” he says. “I see that going well beyond, with what we refer to as cabin health monitoring, where each of the furnishings is able to report where it is and whether it needs repair.”

“Passengers could share information to better allow the crew to personalize services. You can imagine 200 people boarding and offered an option for meal selection, and the crew knows who wants their meal first – that kind of thing. That would all rely on connectivity of airplane to passenger, to crew.”

Connectivity could also facilitate novel experiential enhancements, such as sending aerograms: inflight digital postcards featuring the passenger’s image by the window, the image being a live picture taken by wing-tip cameras.

Beyond these fun explorations, Wilcynski believes there will ultimately be a next-level way to deliver connectivity to the aircraft.

“Whatever happens, there has to be more availability, more seamlessness. Like certain consumer products, it has to be just a download of software. It can’t be that you have to swap out boxes to increase functionality,” he says.

Organic evolution

Overall, Wilcynski sees the flight experience changing gradually and organically for the better over the next 20 years, with few radical changes.

“I think it’s going to be evolution, not revolution. I can’t really foresee a revolution,” he says. “The revolution might be in services provided and how airlines interact with passengers prior to and while on board, and how they deliver meals. That’s what I would see as a possibility of revolutionary change.”

This conservative view of change coming at its own sustainable pace invites questions about some of the more radical design ideas that have floated over the past 20 years – and which continue to fascinate us today.