Obese passengers have difficulty fitting into a single aircraft seat. This is uncomfortable for them, and the passengers around them, and also for the airline, which has to deal with the consequences. In addition to the physical issues with the seating, larger passengers experience a wide range of problems throughout the entire flight journey – from booking tickets until arrival at the destination.

At the moment, 26% of the adult population in the UK are obese, and experts believe that by 2030, this number will rise to 42%, increasing the number of obese adults in the UK to a total of 27 million. With around 100 complaints about seating and around 50 enquiries about special needs a year, this is just the start of the issues surrounding passenger obesity in the airline industry.

A look into the future can be taken when comparing the UK to the USA; according to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, in 2009-2010, 35.7% of US adults were obese, resulting in more than 700 complaints from passengers who felt cramped by “super-sized seat-mates” on United Airlines flights in 2009. To avoid reaching the same problems in the UK that are currently occurring in the US, the situation needs to be addressed as soon as possible, and in a way that is rewarding for all stakeholders.

Current solutions and their shortcomings

At the moment, there are a small number of solutions being employed by airlines to improve the accommodation of larger people on aircraft. Firstly, numerous airlines have implemented policies regarding customers of size (COS). These policies explain the airline’s rules regarding larger passengers and the possible consequences of not following the rules. Most airlines that employ a COS policy require passengers that do not fit into a single seat to purchase an extra ticket. Naturally, this solves the problem of larger passengers impeding on neighbouring seats. However, it doubles the cost of flying for larger people, while these passengers might not require the full width of two seats. Additionally, in a three-seat row, larger couples or families are unable to sit together since they occupy two seats each.

Another common problem faced by larger passengers is their difficulty, or inability, to fasten the seatbelt. Airlines provide seatbelt extensions on board the aircraft, free of charge. However, these extensions are brightly coloured, which causes embarrassment among larger passengers when requesting an extension once on board the aircraft.

Developments regarding wider fuselages and seats are also being made. However, these are not progressing at the same rate the obesity prevalence is increasing. B/E Aerospace and Airbus are experimenting with increasing the seat width of one out of three seats in a triple, at the cost of the width of the other two seats. This is an undesirable solution for two reasons; firstly, because it only provides an extra 5cm on the wider seat, which is not enough to solve the problem of obese passengers impeding on other passengers’ seats, and secondly, the price of the smaller seats stays the same while the price for the wider seat increases. This results in the majority of customers paying the same fare as prior to this development, for less space. This increases the possibility of upsetting the majority of the customer base.

In the future, in addition to the obesity prevalence increasing, the amount of passengers using air transport will also increase. A two-year, global consultation that Airbus conducted among 1.75 million people revealed that 63% of participants believe that by 2050, people will fly more. “The results of the survey show that there is nothing better than face-to-face contact,” says Charles Champion, Airbus’s executive vice president of engineering.

European airlines are already starting to notice this increase in passengers, with a 7.1% increase on the amount of passengers transported in 2011 reported by the Association of European Airlines [AEA] in 2012). Additionally, Ryanair and easyJet have both reported an 8% year-on-year increase in July passenger numbers and the Air France-KLM Group has reported growing passenger revenues of 7%. It is predicted that “the global airline industry will need 33,500 new aircraft before 2030, of which 60% are necessary to extend the existing fleet”, according to Boeing.

The increase in passengers, in combination with the rising obesity prevalence, will naturally result in an increase in larger passengers. Since larger passengers will form an increasingly larger percentage of an airline’s target market, developments and improvements need to be made in order to avoid losing this target group to competitors, and risk losing a big market share and revenue.

The main goal of this project is to improve the flight experience for larger passengers. However, other passenger needs and airline economics also need to be taken into account; ensuring that airlines are not losing profit and business, and passenger’s airline preferences are not, or only positively, influenced. Some of the recommendations will suggest developing new products or services to improve the flight journey of larger passengers, and some will only suggest improvements to existing products and services. How can communication, product and service design be utilised to improve larger passengers’ flight experience?

The right to travel

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights [UDHR], article 13, states that: “(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. (2) Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country” (United Nations, 2012).

However, the UDHR does not state that no special requirements need to be met to travel on certain means of transport. This means that transport providers can come up with any number of (legal) requirements, e.g. paying a fare. The ability for transport providers to make such requirements, ensures that travelling is not so much a human right, but a privilege for the ones that can afford it.

Given the current situation regarding obesity, it can be argued that being large is starting to become the norm and that transport providers should adjust to the changing demographics. Campaigners against obesity discrimination have argued that airlines “must take into account the individual needs of its passengers”, and “a passenger should only have to pay for one ticket”. In order to improve the flight experience of larger aircraft passengers current issues need to be analysed.

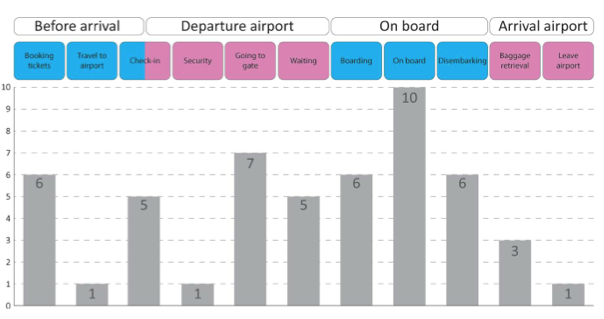

Figure 2 illustrates the level of difficulty that larger passengers experience during the different stages of the flight journey.

From this diagram, it can be concluded that there are three main problem areas in which larger passengers experience difficulty during the flight journey; booking tickets, on board issues, and walking, boarding and disembarking.

Ticket booking issues

Booking tickets has been identified as a problem because not all airlines provide information regarding their COS policy on their websites, making it unclear to larger passengers if the airline has a policy. A COS policy explains the airline’s rules regarding larger passengers. Most airlines that have such a policy require passengers that do not fit into a single seat to purchase an extra ticket.

In addition to not providing this crucial information on their websites, many airlines also do not provide the seat dimensions on their websites, or the option of purchasing two tickets in a single online booking.

To explore the final perspective regarding the growing obesity prevalence in the airline industry, several interviews and questionnaires were conducted with obese and ‘standard size’ people. Also, an observation of a larger passenger on an aircraft was included. 90% of questionnaire participants did not know if the airline they most commonly travel with has a COS policy. As a result of this unawareness of the COS policy, larger passengers may only purchase a single ticket when they require two, in line with the airline’s COS policy. This can result in uncomfortable situations once at the airport. It also means that larger travellers might face extra costs they were not aware of when booking the flight.

Apart from the unawareness regarding COS policies among ‘standard size’ and larger passengers, the absence of information from the website and the booking process results in larger passengers having to call the airline for more information and to book their tickets through the telephone. Not only is this unnecessary and discriminating for larger passengers, it also results in extra costs for the airline, having to employ staff to deal with an increasingly common request.

The experiences of obese travellers in regard to booking tickets, seat dimensions and COS policies showed themes of embarrassment, fear and discomfort.

Booking process comparison

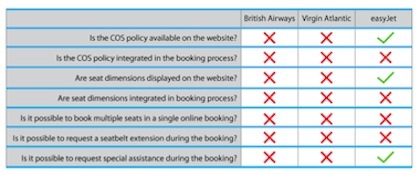

Figure 3 visualises what elements, regarding larger passengers, are implemented in the booking processes of three major UK airlines. It is clear that larger passengers have not yet become a target group that airlines are focusing on.

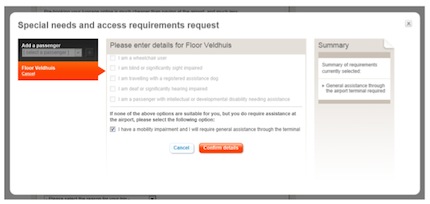

Passengers feel strongly about the COS policy being integrated in the booking process, in order to inform both larger and ‘standard size’ passengers. Larger passengers prefer to be informed of the seat dimensions and select the amount of seats required in the booking process. Also, larger passengers would like to arrange their special assistance needs online without having to call the airline. easyJet’s current method for arranging special assistance online (Figure 4) was described as ‘a lot easier’ than current methods of British Airways and Virgin Atlantic.

Larger passengers also prefer that the option to request a seatbelt extensions is implemented in the online booking process.

Onboard issues

The onboard stage of the flight journey results in the greatest issues, both physically and emotionally. The main issue found in the questionairre, as expected, are the seats. Other problems evolve around seatbelt extensions, tray tables, lavatories, aisles and overhead storage compartments.

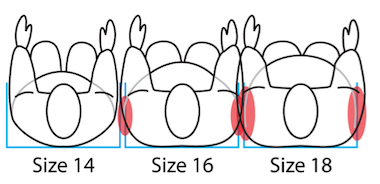

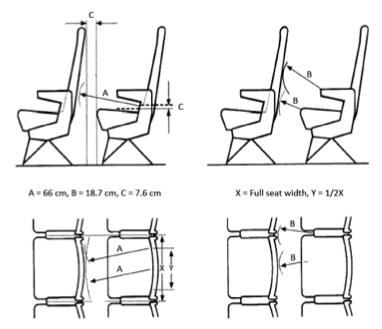

The Mandatory Requirements for Airworthiness, commissioned by the Civil Aviation Authority [CAA], stipulate a minimum seat pitch of 66cm, as illustrated in Figure 5. However, it does not provide a minimum dimension for seat width. This legislation regards safety considerations only and leaves “standards of passenger comfort” up to the airline.

In addition to the missing requirement for minimum seat width, the existing Mandatory Requirements for Airworthiness with regard to seating dimensions are found to be insufficient. “It is recommended that dimension A is increased to at least 71cm to accommodate up to the 95th percentile European seated passenger,” stated Quigley et al in ‘Anthropometric Study to Update Minimum Aircraft Seating Standards’, 2001.

“Between 23 and 25.5cm would be an acceptable minimum for dimension B at armrest level” and “dimension C would need to be increased to 30.5cm to permit a 95th percentile passenger to stand upright”, and to avoid uncomfortable and fatiguing body postures,” stated Quigley et al.

However, the authors recognise that this is “unlikely to be practical on economic grounds” because it would result in increasing the seat pitch, losing a significant amount of seats on each aircraft, which is economically undesirable for airlines.

The smallest seat width on long-haul economy class flights is on Monarch Airlines (Boeing 767-300), at only 41cm. Most airlines provide economy class seats with an average width between 43 and 46cm.

Other UK transport industries do, however, have regulated seat dimensions. The minimum width of UK train, coach and bus seats is regulated to be at least 44cm at the widest point. A great example of the commercial struggle is Lufthansa, with its seat width being around the average, announcing it would “decrease the size of the its aircraft seats so that more passengers could fit in a single aircraft”. This demonstrates once again, that there will always be a conflict in balancing economics and ergonomics, profit and comfort, in this highly competitive industry.

Seatbelt extensions

Although passengers are able to purchase their own seatbelt extensions, there is no guarantee that airlines will allow them to be used. In addition, some airlines use brightly coloured extensions which can attract attention to the obese passenger for being unable to fit the normal seat belt, making the experience of having to ask for an extension even more embarrassing and noticeable. Airlines argue that the seatbelt extensions have bright colours so that they can be easily located by cabin crew to be tidied away after arrival at the destination.

Also, using a seatbelt extension prevents a passenger from sitting in an emergency exit row, which would be desirable for larger passengers since this offers extra legroom. Airlines state that a seatbelt extension could form a tripping hazard in case of an emergency, and therefore do not allow passengers using an extension to sit in emergency exit rows.

In addition to the seats and seatbelt extensions, using tray tables on board the aircraft poses another obstacle for many larger passengers. One-third of larger questionnaire participants indicated that they experience ‘extreme difficulty’ using the tray table. The remaining two-thirds indicate experiencing ‘some difficulty’.

On top of the aforementioned issues larger passengers face on board aircraft, are others, such as the width of the aisles, using the overhead storage compartments, and using the lavatories.

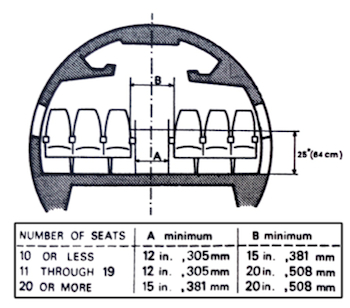

The aisles of aircraft carrying more than 20 passengers have two legislated minimum widths. These dimensions only apply during the take-off and landing stages of the flight, to ensure sufficient escape routes. The minimum aisle width dimensions are: 38cm until 64cm off the ground and 51cm above that, as visualised in Figure 6.

One-third of obese questionnaire participants indicate they experience ‘extreme difficulty’ using on-board lavatories, while another third indicate they experience ‘some difficulty’. Additionally, 50% of obese questionnaire participants indicated they experience ‘some difficulty’ placing luggage in overhead compartments. Also, larger people might experience difficulty and discomfort because of the location of buttons and headphone plugs on the inside of the armrest. This positioning makes it difficult to use the buttons and uncomfortable to use headphones.

Emotional issues

Apart from the obvious physical difficulties, larger passengers also face emotional issues on board the aircraft. Before and during their flight they are exposed to the attitude of airline staff and fellow passengers in addition to facing their own insecurities.

All obese interviewees and questionnaire participants indicate never having experienced any problems with other passengers or staff. However, they indicate the feeling of discomfort and negative attention. Personal insecurities are also a big issue since they can make larger passengers feel very uncomfortable before and during the flight, resulting in a bad flight experience. Their main fears are based on seat dimensions and possible consequences such as flight exclusion or being obligated to purchase a second seat.

Walking, boarding and disembarking issues

Walking long distances (e.g. towards a remotely located gate) can pose a big problem for larger passengers. 50% of obese questionnaire participants experience difficulty walking, which causes them to move more slowly than other passengers which, in turn, is made even more uncomfortable and stressful by the fact that there is limited time to get to the gate from the moment the departure gate is announced. These factors can result in an unpleasant experience because larger passengers rush and fear they will not reach their gate on time.

Boarding and disembarking the aircraft is also harder for most larger passengers. One-third of questionnaire participants indicate experiencing ‘extreme difficulty’ and another third indicate experiencing ‘some difficulty’ with walking the steps to board the aircraft.

Additional findings with regard to the second problem area for larger passengers are queuing to board the aircraft and sitting in the waiting area. About one-sixth of obese questionnaire participants indicate they experience ‘some difficulty’ with these elements of the flight journey.

Safety and disability

Every newly developed aircraft seat has to endure three tests before being approved: a forwards 16G test which involves airframe twisting, ensuring that no part of the seat disconnects from the seat tracks; a 9G downwards test which involves measuring the forces on the dummy; and a hick test, simulating an emergency landing at a 15° angle.

The CAA increased the standard male passenger mass from its initial 79.4kg to 87.6kg in 2005. However, according to the US National Centre for Health Statistics, the average man in the USA weighs 88.5kg, while, a dummy weighing 77.1kg is used to test new seats.

Not only are seats under-tested, they are also being overloaded. “If a heavier person completely fills an aircraft seat, the seat is not likely to behave as intended during a crash”, said Salzar in the ‘Big Issue’ feature in the June 2012 issue of Aircraft Interiors International). This results in not only jeopardising the life of the larger passenger, but also the other passengers in close proximity.

Experts from the airline industry believe that redefining the size of the dummy would potentially have a very big influence and that it would become increasingly difficult to pass the tests without increasing the weight of the seat. However, if the authorities were to redefine the weight of the dummies, everything that is already flying is legitimate because you cannot go back historically.

This means that there is, apart from the fact that an aircraft has to be evacuated in 90 seconds, another reason to urge larger passengers to purchase two seats: to spread their weight over two seats in order to get closer to the dummy weight per seat.

The trend at the moment is to widen the centre seat instead of window or aisle seats because it is perceived that the middle seat is the least attractive seat. However, it would probably be best to place larger passengers in window seats as not to block the rest of the row in case of an emergency.

Other safety features that are not designed for use by large passengers are seatbelts, life jackets, emergency evacuation slides and emergency exits. All these products are tested with the 50th percentile dummy, meaning that they may not be sufficient for larger passengers.

People’s physiques are becoming more and more diverse. As a result, airlines have to cater for passengers with all sorts of requirements, from wheelchair users to vegetarians, and are expected to accommodate personal requirements and requests.

Disability regulations

Also, “airlines may not refuse transportation to people on the basis of disability” according to the US Disability Discrimination Act. Airlines can exclude someone from flying “if carrying the person would be inimical to the safety of the flight”, according to the United States Department of Transportation. This means that airlines can only refuse to carry larger passengers if they pose a threat to the safety of the flight.

Airlines can, however, choose to locate certain passengers in convenient seats as to avoid them posing a safety risk. This is already being done by not allowing disabled passengers to sit in emergency exit rows.

Because safety is the only acceptable reason to place a passenger in a particular seat, this can also be considered for larger passengers. This is already being done by excluding larger passengers using a seatbelt extension to occupy a seat in an emergency exit row. However, this could be taken even further to the point where large passengers are positioned close together as to avoid them posing a safety risk for other passengers.

The latest disability regulations for all aircraft flying in, to and from the USA, were implemented in 2009 and include accessible lavatories, movable aisle armrests, provision of on-board wheelchairs, and space to store wheelchairs and other mobility aids in the cabin.

Existing solutions

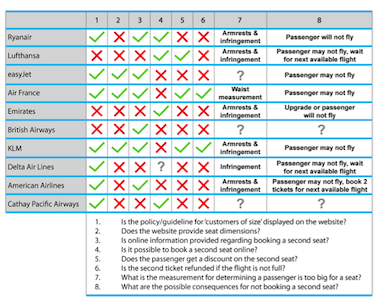

As mentioned above, some airlines use a COS policy to better accommodate large passengers on flights. In order to analyse existing policies and guidelines for accommodation of larger passengers on aircrafts, the top 10 world’s largest international carriers (according to the CAPA Centre for Aviation) are compared, based on eight criteria, and visualised in Figure 7.

Existing policies

Most airlines display their COS size policy on their website. However, primary research shows that 90% of questionnaire participants are unaware of the existence of policies regarding larger passengers. Also, some airlines chose not to use generic policies.

In addition, most airlines do not provide seat dimensions on their website, making it difficult for passengers to determine if they require two seats. Almost all airlines in the comparison provide information about booking a second seat on their website, but only a handful of these provide the option of booking two seats online. There are very few carriers that offer a discount on the second seat or reimburse the passenger for the second seat when the flight is not fully booked.

44% of questionnaire participants feel that waist measurement should be the deciding factor when determining if a passenger is too big for a single seat, and most interviewees agree. Surprisingly, half of the airlines use the armrests and infringement of the adjacent seat as a reference.

Case studies; different modes of transport

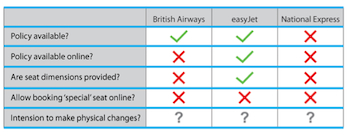

Figure 8 visualises the results of conducted case studies among three different transport providers, comparing the implemented policies, seat options and future developments regarding larger passengers.

Even though all case study subjects indicate they have noticed a rise in larger passengers, they withhold information on whether or not they are making or planning to make any physical changes to accommodate the changing demographics. National Express clarifies that it does not develop its own trains and buses and is therefore dependant on external designers and manufacturers to implement changes. On National Express buses, a ticket guarantees a seat but does not reserve any particular place. The trains however, do use seat reservations. This poses a problem when a passenger does not fit into a single seat, as it does on airlines.

Different stakeholder perspectives

Airlines face a growing number of larger passengers, and therefore presumably a growing number of complaints as a result of the compensation economy. In the USA, where obesity is an even bigger problem, this is happening already. In 2009, United Airlines received more than 700 complaints from passengers who felt cramped by the larger person sitting next to them.

With these figures in mind, it is no surprise that airlines are trying to protect themselves against negative publicity and claims caused by uncomfortable seating situations. They state that COS policies are in place for passengers’ comfort and use fast evacuation of a flight as a public argument.

Most airlines now use COS policies to accommodate their larger passenger; however, some airlines try to do more for their passengers and initiate schemes, such as offering a second seat at a discount. This sort of policy is suggested by the UK Department for Transport, which states, “air carriers should consider offering the second seat at a discounted rate where, because of the nature of their disability or reduced mobility, a disabled person or person with reduced mobility requires two seats.” Some airlines go another step further and reimburse the passenger for their second ticket if the flight is not full.

Competitiveness and differentiation are the main drivers for airlines. Empathy and flexibility regarding larger passengers can be perceived as a brand strength, and can be used as a unique selling point in differentiating from competitors.

On the other side of the argument are the campaigners against obesity discrimination. They feel that airlines must take into account the individual needs of their passengers, and that passengers should only have to pay for one ticket.

The larger passenger perspective

In Canada, all airlines execute a one-person-one-fare policy (1P1F), as a result of a court ruling. However, in order to qualify, passengers have to demonstrate objective evidence of ‘activity limitations and/or participation restrictions.’ This means passengers have to obtain a doctor’s approval before utilising the 1P1F policy.

Even though letting doctors determine a passenger’s size is probably the fairest way, it is also undesirable since the UK’s NHS, for example, is already under pressure as a result of the increasing obesity prevalence.

The general public perspective

The final perspective that needs to be taken into account regarding this matter, is the opinion of the ‘standard size’ passengers, the general public. Almost one-third of Ryanair passengers voted in favour of charging excess weight fees for very large passengers in 2009. A second poll showed that 46% of passengers think the best way to charge for excess weight is to charge per kg over 130kg (male) and 100kg (female).

This way of charging passengers however, will only benefit the airline by making up for the extra fuel costs, which is not the actual problem. If a passenger is charged because he/she weighs more than a set limit, but is still seated in a single seat, the situation is not in any way improved. However, some members of the public have expressed that they feel that having to pay for excess weight of luggage is unfair, when COS are not charged extra for bodily weight.

It can be concluded that the passenger perspective is that there needs to be a balance; larger passengers should pay more, but should also receive more space for the extra money they spend. This is to the advantage of all passengers as well as the airline.

Existing seat options

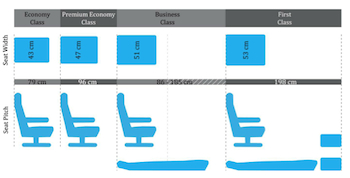

Most aircraft are divided into two- or three-class configurations, accommodating different passenger requirements. To analyse the differences between travel classes, Figure 9 was drawn up. The image clearly shows the difference in seat pitch (and thus legroom) and seat width.

In addition to more space, upgrading travel class also entitles passengers to extra services and privacy. Where in economy class passengers generally receive minimal service, premium economy has extra benefits such as a larger recline, a premium meal and a separate cabin with fewer people. When upgrading to business class or first class the difference becomes even more apparent. Passengers in business class receive an even more premium meal, seats that recline to a lie-flat bed and all sorts of facilities that enable a better work and relaxing environment. First-class passengers receive an even more extended package which can include a private cabin, staff making their beds, pyjamas, toiletries, showers, a mini-bar and a personal wardrobe.

Larger passengers are urged to purchase an upgrade or second seat by many airlines. However, these passengers only require extra space, not extra service, and they do not wish to pay for extra services. It seems that the current seating options are insufficient for the diversity of passenger needs. Perhaps airlines might offer more diverse service packages in the future to offer more flexibility.

Although some experts feel that the rising obesity prevalence is not noticeable in the airline industry, others disagree and feel it comes up quite a lot in seat and cabin design, even though no changes have been made yet.

Existing services

Some larger passengers use special assistance to make their flight journey more comfortable. The current process for requesting special assistance is for the passenger to call the airline and inform them of their requirements. The airline then contacts the airport operator, which then hires a company to take care of the special assistance requests from all airlines at the specific airport.

Airlines pay a fee for special assistance services for every departing passenger, regardless of how many of them require special assistance. Services that are provided include transport through the terminal, check-in, security, transport to the gate and placing the passengers on the aircraft. Special assistance is available to all passengers, regardless of their physical or mental situation.

50% of questionnaire participants feel that no separate service is required and that larger passengers can be assisted through the existing services if necessary. 50% of questionnaire participants also feel that anyone requiring special assistance should be able to use the services for free, regardless of their impairment. 33% of questionnaire participants argue that since obesity is self inflicted and reversible, larger people should be charged for using special assistance as opposed to passengers who are not responsible for their disabilities.

In order to improve the flight experience of larger aircraft passengers, solutions for the three problem areas of booking tickets, on-board issues, and walking, boarding and disembarking must be consistent across all touch points and developed according to user-centred design, to deliver an optimal customer experience.

Communication design and the pre-boarding stage

From the findings it can be concluded that most airlines employ a COS policy to accommodate larger passengers. However, they seem to experience difficulty in communicating the policy to passengers. Since some airlines do not display their COS policy on their website, and none of them include the policy in their booking process, it allows passengers to assume that the airline does not use a COS policy. Since in this case passengers will not comply with the regulations, it can result in uncomfortable situations at check-in, or on board, and possibly lead to flight exclusion.

Almost 90% of passengers feel that implementing the COS policy in the online booking process would help larger passengers to book the right seats. It would inform the larger passengers of their responsibilities and create an understanding for the situation among other travellers. Also, it would remind larger passengers that they may vary too much from the model user to be able to use the same service.

A COS policy generally entails information regarding responsibilities for the passenger, suggested actions, and possible consequences for not following the policy. Most airlines urge passengers to recognise ahead of time they might need two seats when travelling in economy class, but fail to display the dimensions of the seats.

Larger passengers that are aware of airlines using COS policies feel it is undesirable and unnecessary to have to call the airline for information about the policy and if necessary, book two tickets or special assistance over the telephone. Using online technology and digital touch points is increasingly important in everyday life.

Additionally, allowing larger passengers to book their tickets and other requirements through the standard online booking process, like every other passenger, would benefit airlines. They will receive fewer phone calls about an increasingly common issue which, in turn, will result in fewer man hours and therefore a cost reduction.

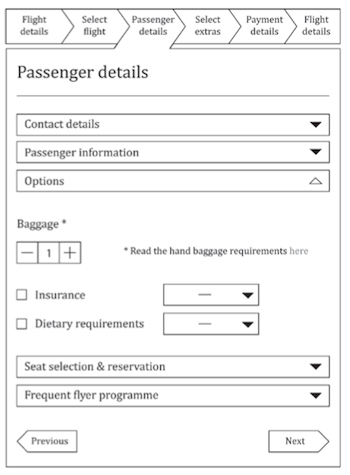

It can be concluded that it would be beneficial for all parties involved to include the COS policy in the booking process. In addition to this information it would also be helpful to display the seat dimensions of the different travel classes. Larger passengers who completed the questionnaire also indicated that they would prefer to request seatbelt extensions and special assistance during the booking process to avoid having to call the airline, despite implementing the option of booking two tickets online.

50% of questionnaire participants feel that part of the policy should be implemented in the ‘flight details’ section of the booking process and part in the ‘passenger details’ section.

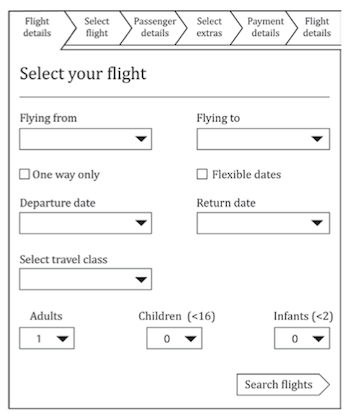

In general, the flight details section of the existing online booking process looks similar to the visual in Figure 10.

It is recommended to implement the required seat quantity per passenger in the ‘flight details’ section. This allows people requiring more than one seat to get an accurate price calculation in the ‘select flight’ section. Also, this makes all passengers aware that the airline is taking the issues regarding larger passengers seriously, which will create a better understanding from the ‘standard size’ passengers.

Strategy for improved communication

Additionally, it is recommended to implement the option for passengers to read the COS policy during the booking process, including the seat dimensions. However, the options for larger passengers should not take too much space and time in the booking process since the biggest customer group is still formed of ‘standard size’ passengers. Therefore, it is recommended to implement these elements whilst allowing minimal effect on other passengers in order to improve usability.

The other elements required by larger passengers, such as seatbelt extensions and special assistance, can be implemented in the ‘passenger details’ section of the booking process, visualised in Figure 11. It is recommended not to make this a part of the core steps of the booking process, but to implement it in combination with other ‘options’ such as insurance and dietary requirements. This way, larger people can avoid having to call the airline, but ‘standard size’ passengers will not be affected. Also, airlines will be informed of passengers’ special assistance requirements more than 48 hours before the flight, which allows them to have a better overview of the special assistance requirements.

In conclusion, larger passengers want to be treated like all other passengers. Therefore they would prefer to arrange all their requirements online, like everyone else. The strategy that should be employed to deliver an optimal flight booking process for larger passengers, whilst minimally affecting ‘standard size’ passengers, can be achieved by applying communication design. The elements regarding larger passengers should be divided over the ‘flight details’ and ‘passenger details’ sections of the booking process.

See part two for product design and the onboard stage, concepts and recommendations