The launch of Aircraft Interiors International magazine in 1998 coincided with a turbulent time for the aviation industry: the global economy was lurching disconcertingly, fuel prices had begun to rise sharply, and competition in the skies was increasingly fierce. Every major airline was scanning the horizon to locate the point of difference that would give them a business advantage.

In 1998, British Airways (BA) presented a daunting challenge to Tangerine: “Find us the holy grail of airline travel sprinkled with a bit of pixie-dust – and astound us along the way.”

BA’s director of marketing at the time, Martin George, says the airline wanted “something that was genuinely different and distinctive”.

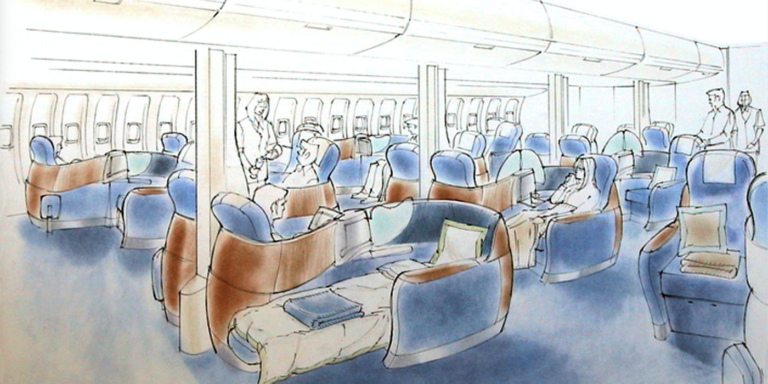

The response from Tangerine to the BA brief was Project Dusk, an audacious design that would stun the aviation industry, redefine the business market, and become the profit engine for BA. “It was something many regarded as simply impossible,” says Tangerine CEO, Martin Darbyshire – nicknamed ‘the Professor’ by executives at BA because of his technical know-how. “We came up with a totally lie-flat bed in business class that kept the same number of seats while enhancing the very special BA brand.”

Intensive development

It was a hard-won pitch. For weeks, Tangerine’s chief creative officer Matt Round had made the company offices resemble a dormitory after an earthquake: there were modeled beds everywhere and at every conceivable angle – slanted, end to end, side by side, on top of one another.

“It’s essential to have something physical to feel and make one aware of how spacious or cramped something feels,” Round explains. “It is amazing how different things appear when they are physical and how dramatically they can shift your perceptions.”

Project Dusk was about understanding the psychology of the business passenger as much as the practical constraints of an airliner. A sleep expert, recruited to advise Tangerine, explained that the average person turns over in bed 30 times a night. If you can’t turn in your airline seat, you never reach deep sleep, they were told. And the key to turning over was lying flat.

Yin yang

There wasn’t a sudden ‘eureka’ moment of the project, although the answer, when it came, was groundbreaking: the yin-yang approach. From the apparent chaos of Round’s model beds emerged a formation that would redefine the design of aircraft interiors. Instead of all passengers facing the front of the cabin, seats were paired in a forward/rearward formation.

“No one had ever arranged cabin space in this way,” says Round.

The yin-yang approach allowed the design team to consider new ways of using cabin space: armrests could be positioned over each other; the footstool could be separated from the seat to give more freedom of movement; and a lower, reclined seat geometry offered a more welcoming environment when boarding.

“Passengers told us they yearned for the freedom to move as they wished,” Darbyshire explains. “This design allowed people to move around and feel special. We were offering a lounge in the sky.”

The team had indeed uncovered something unique – a fully flat, 6ft bed that still kept eight seats abreast in a B747.

Martin George remembers the moment when Tangerine unveiled it to the airline’s in-house team. “The reaction was ‘Wow!’” he recalls. “People thought ‘this is amazing’, that it could deliver the crown jewels – but I was actually very nervous. We had yet to convince the BA board.”

Convincing the board

It was a huge decision for the airline. Should they spend millions on an untried concept for their business class cabins at such an uncertain time for the industry?

“It had never been done before, and it was a calculated risk with enormous implications,” says George.

Experts from across BA’s operation worked closely with Tangerine to help get the project to fly. It was a testing time in more senses than one. The project team had to be confident the new seats were robust enough – any technical failure could have been disastrous.

“On the New York route, for example, there would be 96 Club World seats,” Darbyshire notes. “At 32,000ft, you don’t want them going wrong.”

Tangerine worked with the seat manufacturers for five months as the first prototypes were produced, putting the seat through a wide range of dynamic tests. It wasn’t simply the engineering that had to be considered. Early research suggested some passengers might feel uncomfortable flying backward – a psychological barrier to the yin-yang design. “My gut feeling was that it would work,” Darbyshire recalls, “so BA proposed research conducted in their lounges.”

While they waited for the results of the survey, the Tangerine team were taking to the skies themselves. Trial flights with the UK’s Royal Air Force were arranged to reassure the doubters that people wouldn’t suffer motion sickness when flying backward. The exercise demonstrated that, unlike a car or a train, where a passenger relates to the landscape outside, a large passenger aircraft is not close enough to anything for travel sickness to be a significant problem.

When the in-depth survey from BA’s lounges had been collated, the results showed only one passenger in 100 was opposed to the idea of facing backward, and they would have plenty of forward-facing seats to choose from. Yin-yang was still on the table. Everything now depended on convincing the BA board.

Martin George still remembers the trepidation mixed with excitement as he prepared to present Project Dusk to the airline’s executives in the form of a foam mock-up model. “We’d done

the research and then we just had to push it. Half a dozen of us walked the board through every detail.”

There was nervousness, too, at Tangerine, where everyone was waiting to hear the decision.

At a launch ceremony in a London TV studio, BA’s then CEO Bob Ayling explained how the airline was basing its future on the results of extensive research into what frequent flyers said they wanted. “They wanted us to be the best in the world,” he said. “So do we.”

The dream becomes reality

Fifteen months from the beginning of the project, the first fitted airplane was in the sky. “Pretty pacy by any standards,” as Round puts it. But Project Dusk was never rushed. “Looking for any quick result under pressure is not going to work. You have to have the space to play around.”

Passengers fell in love with the lounge in the sky. The cabin crew championed it. The board saw

a return on their investment within 12 months and shareholders were delighted.

“It is among the most innovative things the aviation industry has ever done and it changed the way the business world thinks about flying,” says Round. “Prior to that, everyone was flying all night sitting upright. Now you wouldn’t think of it.”